He was like Nureyev among clog dancers; like Shakespeare competing with the writers of dime novels; like the difference between Einstein and a first-year chemistry student at a small, insignificant college.

He was like Nureyev among clog dancers; like Shakespeare competing with the writers of dime novels; like the difference between Einstein and a first-year chemistry student at a small, insignificant college.

Pete Maravich was that rare bird among noted basketball players of the last 50-odd years: A White guy who was so gosh-awful brilliant that he could do things on the court no one else has done, before his time, or since. He was the guy who changed NBA basketball from a disciplined but sometimes boring, heavily-coached game, to one in which a guy with an unlimited imagination and superb control of the ball, could paint his own canvas, in his own way, like Rembrandt in a moment of divine inspiration.

Pistol Pete (an apt nickname, which stuck to him when he was very young and had to shoot baskets from the hip because his arms were not yet strong enough to get off a jump shot; he looked like he was drawing a gun from a right-side holster), set the NCAA college basketball career scoring record of 3,667 points, in just three years at Louisiana State University, where his dad Press Maravich was the coach. Freshmen weren’t allowed to play varsity ball during Pistol Pete’s years in college, 1966-’70; and there was no three-point shot, either. He did it all in three seasons, with only two-pointers and free throws, and averaged 44.2 points per game for his career while doing it. Both marks still stand as the best of all time in the NCAA. They probably will, for a long time.

But big-time scoring wasn’t the only thing Pistol Pete could do. A number of NBA veterans called him “the best ball-handler of all time.” Dribbling behind the back, between his legs — even on occasion between the legs of the man guarding him — was all in a day’s work for Maravich, who pioneered the concept and the style, “Showtime.” His passes were breath-taking, eye-popping, and often hard to follow because they came so suddenly and unexpectedly. Pete sometimes threw a hard pass behind his back to a teammate suddenly open under the basket, for an easy score. The behind-the-back style not only brought gasps and cheers from the crowd in the gym; it also threw his defensive man off stride as a straight chest pass which could have been intercepted would not have. Pete also gave numerous defensive men “broken ankles” (figuratively speaking) with his lightning-quick crossover dribble. The Pistol went off full-bore; his speed and quickness always made him hard to stop.

Pete wrote his own playbook when it came to being a virtuoso on the court. He might throw a bounce pass almost the length of the gym to a fast-breaking teammate for an easy two points. Or, in a similar situation, he might grab a defensive rebound, spin, and heave an underhand lob the length of the court — right into the hands of another speeding teammate who swooped in for an easy layup.

If he was racing in for a layup himself, and suddenly there loomed a huge, opposing center between him and the basket, long arm extended straight up in his face, Maravich could switch gears in a nano-second and toss the ball high up on the backboard — too high for even an NBA gorilla to block. The ball would kiss the top of the backboard gently, and drop straight down — nothing but net. When Pete Maravich had his hands on the ball, the ball knew who was in charge, and that it had better do what it was supposed to.

A friend who saw Pete play with the New Orleans Jazz told me that once in a game he was watching, Maravich grabbed a defensive rebound, took the merest glance downcourt, then tossed what looked like a hard hook shot against the opponents’ backboard, just above where he was standing. My friend said the ball rebounded off the board with a loud “Splat!” and flew downcourt — and right into the hands of a teammate of Pistol Pete’s who was breaking for the basket. My friend said he’d never seen a player do a maneuver like that, before or since.

And he also said something else that was quite interesting, in this era when most young people assume that the NBA players were always mostly black. “The black fans loved Pete — just LOVED him!” my friend said. “He took the types of plays originated by the Globetrotters, and moved them to a different dimension.”

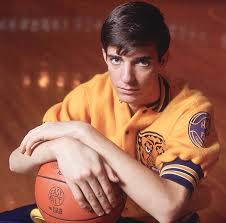

Pete was a lanky, 6-5 guard, famous for the “floppy socks” he always wore while playing, and his mop of late-’60s, collar-length hair. Pete’s face, in repose, featured a pair of sad (maybe the coeds at LSU said, “soulful,”) eyes. He didn’t smile a lot; although when he did, the grin lit up his face and the sadness disappeared from his eyes — briefly. But most of the time, The Pistol remained poker-faced. In a game where acrobatic, self-aggrandizing slam dunks, strutting, yelling and getting “in the opponent’s face” — that is to say, egotism gone crazy — have become commonplace, Pete almost never showed much emotion about his field goals, nifty passes, or dribbling. He just did them, turned, and headed back down the floor.

Pete’s dad Press had played basketball, very well, in high school, then became a basketball coach himself after high school, World War II military service, and college. Pete was born to Press and his wife, Helen, on June 22, 1947, in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, Press’s hometown. Press started teaching Pete how to throw a basketball toward — and hopefully through — a small hoop when he was 3 years old. Small ball, too, so Pete could handle it. Press’s basketball gene had been passed on to his little boy. He said later that when Pete threw the ball the first time, and missed, he started to get mad, picked up the ball, tried again, and again, and again …

Pete spent all the time he could spare from eating, sleeping and school, on honing his skills with the roundball, from that day on. Practicing every kind of shot there was; working on behind-the-back dribbles, pinpoint, eccentric passes, on anticipating an opponent’s move to try to make more steals on defense, and every other avenue of the hardwood game that one could think of. A childhood friend recalled how when he and Pete would go to the movies, Pete would take his basketball along, practice dribbling “in place” in the aisle (he always sat in the end seat) with his right hand for a while, then he would switch to a seat at the left end of the row so he could practice with his left hand, too. He wanted to be ambidexterous in his chosen sport. Without that ability in basketball, your defensive man can overplay you to your weak side. Pistol Pete was determined that he would have no “weak side.”

There were a few times when Press had Pete get in the family car, and as Pop drove slowly down the street, Son dribbled his basketball on the concrete, with his arm out the window. The records do not show whether they encountered any of Aliquippa’s finest while doing this; if they did, Press probably got a strong talking-to.

But even as a child, Pete was one of those rare people who always did it “his way.” And who was grimly determined that he was going to be THE BEST, that he was going to make a million dollars, and win a championship. There is an old saying: “To a genius, NOTHING is ‘too much trouble.’ ” When it came to basketball, that was Pete, all over.

After an outstanding high school career, Pete followed Press to LSU, where the elder Maravich had been named head coach. In his sophomore year, when he joined the varsity, Pete burst on the U.S. basketball scene like the brightest comet you’ve ever seen. For the next three years, his exploits on the hardwood were the stuff of reams of copy for sports writers, of more telecasts of LSU games than the football-oriented school had ever had in its entire history — and of criticism from some opposing fans, some sports writers, some coaches, that he was a “hot dog,” a “selfish” player who wanted all the shots himself. But that was what Press wanted him to do. He felt that without Pete shooting at least 40 times a game, the LSU Tigers couldn’t win.

The Tigers never won a championship, NCAA or NIT, during Pete’s three years — a jinx that would follow him throughout his career. But he set those scoring records mentioned above, and signed an NBA contract with the Atlanta Hawks. His salary, spread out over several seasons, was $1.5 million, the highest ever in the NBA up to that time. That, and his reputation (deserved or not) for being a ball hog and a show-off, didn’t sit well with the veterans (mostly black) on the Hawks. They apparently saw this “White boy” as being favored mainly for his race. As a result, Pete’s time with the Hawks was not happy for him, although he repeatedly showed his brilliance at the game and gradually won the grudging respect of those teammates.

Eventually he was traded to the New Orleans Jazz, and during his time with them he had his best game as an NBA star, scoring 68 points against the New York Knicks during the 1976-77 season. It was his masterpiece — the most points ever scored by an NBA guard up to that time. Among the Knicks who tried and failed to stop him was Walt Frazier, considered one of the best defensive guards in the NBA. That season, Maravich led the league in scoring with 31.1 points per game, scoring 40 or more points 13 different times.

But Maravich received a severe knee injury in a game later that season, and even after a lengthy recovery period that included surgery on the knee, his speed, quickness and agility were never quite the same again. In January 1980, the Jazz placed him on waivers, and he was picked up by the Boston Celtics. But because of continuing problems with his knee, and because he and the coach did not agree on a number of things about how the Celtics should play, Pete had to sit out a lot of the season, and when it ended, he regretfully retired, depressed that he could no longer play as he once did when he was the most exciting, creative player in the game, and because he had never managed to play on a championship team.

Pete retired to a brooding, frustrated family life with his wife Jackie and their young sons, Jaeson and Joshua. Two years after he retired, he was tossing and turning in bed one night, unable to sleep, and he finally got up, knelt down in the bedroom, and began a fervent, desperate prayer to God to help him. Clear as a bell, he heard a sonorous voice speaking to him. Pete Maravich became a devout, converted Christian in that moment, waking up his wife to ask if she had heard the Voice, with her insisting that she had heard nothing, and going back to sleep.

But Pistol Pete was a new man, and for the remaining five years of his life he spoke in churches, at revivals, and anywhere else that people would listen to his message of salvation. He worked just as hard for the Lord as he had at becoming “the greatest” in basketball.

Pete had said once in an interview that he didn’t want to “play in the NBA for 10 years and then die of a heart attack at age 40.” Eerily, that is just what happened. On Jan. 5, 1988, he had just completed playing in a pick-up game at a church gym when he suddenly collapsed on the floor. Frantic and extended efforts to revive Maravich were unsuccessful. A sudden, massive heart attack had made his statement from years before, a sad and gruesome reality.

An autopsy conducted on Pete turned up an amazing, nearly unbelievable fact: Pete Maravich had been born without a left ventricle to his heart. His right ventricle had somehow grown around the heart and provided the unlimited speed, quickness and energy that he brought to his game — until it finally gave out.

Maravich’s family was devastated by his death, naturally. His father and mother both had passed away in recent years. The news passed like a shock wave through the world of American sports.

And the tributes poured in.

Rick Barry: “He was the greatest ballhandler I ever saw in my life. He could do things with the basketball that were unbelievable …”

Magic Johnson: “He was a great scorer and a great passer at the same time … He was so ahead of his time.”

Isiah Thomas: “Pistol was a big influence on me … What he did on the court was things that players today STILL can’t do.”

Dave Cowens: “When he had the ball, anything could happen. He was born to play basketball.”

And last but definitely not least, Richie Guerin, Pete’s coach in Atlanta: “He would want to be remembered as a good father, a good husband, and a good Christian.”

3 comments for “Pete Maravich: The Mozart of the Hardwood”