There aren’t too many people still living who knew Tony and Rubye Engle. He’s been gone 30 years; she, 44.

There aren’t too many people still living who knew Tony and Rubye Engle. He’s been gone 30 years; she, 44.

Yes, they were my folks. They were the two most important people in my life, and they didn’t have it easy. They made a crucial economic mistake after years of fairly secure life with Dad working for others, and Mom being a stay-at-home housewife and, later, mother. And that baby who finally arrived 18 years after their marriage — who grew up to be Old Corporal — wasn’t nearly as good a son as he could have been — and should have been — to those two good people who worked so hard and made so many sacrifices.

Two farm kids, growing up hard

But then, many people in their day faced lives of such toil and hardship that many people couldn’t imagine enduring them nowadays. Life wasn’t easy for two farm kids, both born in 1904, Mom in Trimble County, Kentucky, Dad in Ripley County, Indiana. My paternal grandfather, Will Engle, devoted his entire life to his farm near Napoleon, and his family. His wife, Lucinda Shouse Engle, raised five children (including a set of boy-girl twins), kept house, cooked, canned, tended a garden — all those things that farm wives and mothers did in those days when family farms numbered in the millions in America.

Allen E. “Allie” Wingham, Mom’s father, and her mother, Elizabeth Richmond Wingham, were farmers, too, on a piece of land near the headwaters of Canip Creek in Trimble County. The Winghams were believing Christians, and so they obeyed the biblical admonition to “be fruitful and multiply.” Grandma was pregnant 15 times. She miscarried one baby, and their oldest son caught a fever shortly after birth and died after just 10 days of life. But the other 13 grew up hale and hearty, helping their parents on the farm and in the home, having their little spats and aggravating each other occasionally as is common in big families, but generally learning to love and help one another in what was not an easy life.

In about the year 1918, Allen Wingham felt the call to become a Methodist minister. In those days, a man could take a correspondence course through the mail, undergo an examination by a panel of senior ministers, then be ordained. So that’s what Grandpa did. And at about the same time, he and Grandma decided to move their brood (the oldest two already married and moved out, eight still at home, three more yet to be born) to the Madison area. One of their sons, Ray Wingham, related in a partial biography he wrote many years later how he remembered riding on the wagon with Grandpa, Grandma and the other younger children, aboard a ferry boat going over to the Indiana side.

Both missed out on high school

Meanwhile, Dad reached high school age at Napoleon and began his freshman year. But the following spring, well before school was to end, Grandpa Engle made him quit school to stay home and help with the spring plowing and planting. Dad’s only brother, Ora, had enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, as America had entered World War I in 1917. Dad’s hands were needed more on the farm than they were writing down sums in a notebook, Grandpa decided.

Dad missed enough school that the next year he was held back as a freshman, again. And sure enough, the following spring, he was made to leave school early to help on the farm — again. He turned 16 in April of that year, and, disgusted with trying to be both a farm hand and a student, he quit school.

Meanwhile, in the Winghams’ new home at a farm Grandpa bought in the Madison area, Mom also finished the eighth grade — and that was the end of her schooling. Grandma made her quit school in order to help take care of her six younger brothers and sisters.

I think this may have intensified Mom’s lifelong habit of reading in any spare time she could find. Although she never said so, I think she always felt keenly her lack of formal education. Mom was smart, and I think she knew her life would have been different had she been able to graduate from high school (many kids didn’t in those days). I think she tried to make up for that for the rest of her life by dressing with as much class as she and Dad could afford, by making sure her hair was always styled just so (Mom was tall and very pretty, so it wasn’t that difficult for her to look nice), and by cultivating a way of speaking that eliminated as much of her “Kentucky accent” as possible. She was also very careful in teaching her baby son to talk. To this day, I don’t say “ain’t” or “We was going” or “Me and you,” or other common but grammatically incorrect phrases. And I don’t feel any sense of superiority to those who do. As Dizzy Dean, the famous baseball pitcher and, later, radio sports announcer, once said, “I know I say ‘ain’t’; but a lot of the people who DON’T say ‘ain’t,’ ain’t eatin’!” But it probably DID make it easier for me to become a writer, beginning as a child and continuing right on through to retirement. That, and the lifelong passion for reading that I inherited from Mom.

Leaving the farm for a paying job

Back at the Engle farm in Napoleon, Dad helped Grandpa with the farm work, but he didn’t want to do that for the rest of his life. In about 1922, I think, he applied for a job with Hillenbrand Industries, in Batesville. They made caskets, and hospital furniture. He didn’t get a job working in the plant; not right away. He was hired to take care of and maintain the Hillenbrand family’s private vehicles. And he started out at $16 a week. Sounds like pocket change now, doesn’t it? But I was told once by a friend’s mother (who was only a little younger than Dad and Mom) that it was pretty good money for that era, for an 18-year-old kid.

I don’t remember for sure, but I think Dad acted as a chauffeur for the Hillenbrands, also. Dad never had a driving lesson in his life. He watched his father drive the early cars that the Engles owned, and then at some point, probably after he was earning money off the farm, he decided to buy a car of his own. He saw an advertisement in the Indianapolis Star for a used Model T Ford touring car, at a price he felt he could afford. So Dad went to Indianapolis — probably on one of the trains that ran through Osgood every day — looked up the owner, made a deal, exchanged his money for the car, and started driving home.

Keep in mind that Tony had never driven before! But he managed to get all the way back to the Engle farm, pulled into the barn yard, and stopped the car. Then — the pressure on him had been terrific, out there on the road by himself — Dad couldn’t pry his hands loose from the wheel! He had to yell for Grandpa to come out and help him get “unstuck.”

But Dad was one of those people who are able to learn how to do something, well, just by watching someone else. Once, when he was still on the farm, Grandma took the train up to Detroit to visit her oldest daughter and her husband. As Dad was the youngest child, he was the only one of the five still on the farm. Grandpa was no cook, so it fell to Dad to prepare the meals for the two of them until his mom returned. “I just did what I’d seen my mom do,” Dad told me once many years later. They managed; and many years later, after my mom’s illnesses made it impossible for her to cook or keep house any more, I found out that Dad was, in his way, just as good a cook as she was. Except for baking, which he wouldn’t attempt. I still remember my mom’s butterscotch pie — the best I’ve ever eaten.

When the Clifty Inn was opened in 1924, Mom got a job as one of the first waitresses there. I remember her telling me how once, in the middle of a very busy lunchtime, she was rushing to a table with a big tray of food, with a large glass of iced tea perched too close to the edge. Just as she passed another table where one of the patrons was a man with a very bald head, the tray shifted slightly, the glass up-ended, and the iced tea gushed all over the man’s shiny pate! She said she was so embarrassed she could have died, and that she apologized profusely and ran to get towels for him to dry off with. The man didn’t get mad — amazingly — but she said when the tea cascaded onto his head, he shouted, “Ooooh! That’s cold!!!”

Later in 1924, the Indiana Methodist General Conference transferred Grandpa Wingham to the pastorate at the Napoleon Methodist Church. The Methodists do that; they don’t leave their ministers in one pastorate until they’re covered with moss. Twice during his ministry, Grandpa was responsible for seven small rural churches.

Anyway, as Mom was still single and living at home, she moved to Napoleon along with the rest of her family. I think she got some kind of a job in Greensburg, which wasn’t far from Napoleon.

Mom’s “Mr. Wonderful” — with no staying power

Some time passed, Mom started to become known in the community, and she and this young Napoleon guy, who was tall and handsome, began “keepin’ company,” as they said in those days. They got serious enough that, when he decided to move to Indianapolis to find a job, he promised Mom that when he had saved up enough money, he would come back to Napoleon, marry her, and they would live happily ever after in Indiana’s state capital. Off he went, with Rubye, his young girlfriend, eagerly awaiting word from him as to his situation once he found employment.

And she waited … and waited … and waited. She had no address for him (he was to have found a room when he arrived in “Naptown”), and in those days telephones weren’t omnipresent as they are today. Mom had no idea how to reach her beloved.

Nevertheless, her family was thrilled that she was the “intended” of such a marriageable young man, and assured her repeatedly that she would probably hear from him just any day now.

But she didn’t. And, understandably, Mom began to get angry and resentful at being treated that way by the young man she was convinced she was in love with.

More time passed. Mom was always a devout Christian, and she attended the Methodist church where Grandpa was pastor, every Sunday. One day after the service she became involved in a chat with a young man her own age — a short, stocky farm boy with thick black hair and an engaging smile. They began to look forward to seeing each other at church. Then he asked her out for the first time. Before long, they had become an “item,” to use a modern term. Rubye began to see qualities in this young man that transcended being tall and handsome: His willingness to work hard, his honesty, his ability to be funny and entertaining when he chose. Yes, Rubye decided she could spend a lifetime with Tony Engle. And he had no doubts about her, either.

Well, right in the middle of Tony’s and Rubye’s blossoming romance, “Mr. Wonderful” showed up from Indianapolis, unannounced, one day, and went to see Rubye, as he had said he would. I don’t know if he actually said, “Here I am, you lucky girl!”, but that was the gist of his message: Now that I’ve had some time in Naptown, and done — whatever, you don’t need to know — now we can get married. Sorry about not staying in touch, but I was very, very busy!

Rubye was no fool, and she wasn’t having any of that. Her reply to him was, essentially: “You’ve got your nerve, coming back here after months of no contact at all, and thinking I’ll just fall gratefully into your arms! I’m seeing another guy now — a REAL man — and you can get out of my house, and don’t come back!”

“With this ring, I thee wed …”

So, Mr. Tall, Dark and Handsome disappeared from Rubye’s life. Within a few months, some time in 1927, she and Tony were married. I used to have their marriage license, which I now have misplaced, and I think it said they were married in Greensburg, by a justice of the peace. Why did they not have a church wedding, presided over by Grandpa Wingham, at the Methodist church in Napoleon? I don’t know, and I’m not going to speculate. Everybody who was involved is long since deceased, so it doesn’t matter anyway.

The next year, 1928, Rubye gave birth to a baby boy. But, sadly, he died shortly after birth. Dale William was the name they gave him. He would have been my big brother. If he had lived, he would be 86 years old now. Tony and Rubye were totally devastated by the loss. Not that they ever told me that in so many words; but they waited 17 years before having their second, and only surviving, child: Me. I think they were afraid that they’d lose another baby, and thus were afraid to try again, until they realized that Mom’s fertility years were running out.

Mom’s family — I think especially her sisters — never got over their disappointment that she didn’t “catch” the beau who didn’t bother to keep in touch. One time when I was still a child, and was with one of Mom’s sisters, her husband and their youngest son, my aunt told the whole story (I’d already heard it from Mom), and wound up by saying, “We were SO in hopes that Rubye would marry him! But instead, we got stuck with Uncle Tony!” The words went through me like a knife. I was a reserved little kid, so I didn’t say anything; if I had, and my aunt had told Mom, she’d have slapped me silly, anyway, for sassing an adult. But I never, ever, forgot that implied insult directed at Tony, my dad, from an aunt who I suspect said it in my presence on purpose. By the way, I never told Mom or Dad about it. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings, and I didn’t want her to blow up at her sister the next time she saw her.

But Dad wasn’t dumb, either. In retrospect, I know that he was aware of how many in Mom’s family looked down on him as kind of a “consolation prize.” He never once said anything about it in my presence — Dad was not a man who shared his inner feelings about most things. But at Wingham family reunions, he would go and sit with the other brothers-in-law (Mom’s sisters’ husbands), nearly all of whom he got along well with, and kind of avoid the born Winghams, when possible.

A new home, a new beginning

Mom and Dad had settled in Batesville the same year they lost their baby boy. There, Dad worked in the Hillenbrand plant — kind of a promotion, I guess, from taking care of the family vehicles. He made sufficient income that Mom didn’t have to work outside the home.

Then in 1936, a couple of labor union guys from Connersville, apparently having heard that Dad was a union supporter and staunch Democrat, came to see him and told him they could get him a job at a plant in that city southeast of Indianapolis, if he would promise to support the union. As it involved a much better paycheck, it didn’t take Dad and Mom long to decide to make the move.

Dad worked at a couple of different factories in Connersville between 1936 and 1949. I was born in 1945 — an older cousin of mine tells me that she and her mom, my mom’s sister, were there for my “arrival”, and that Mom and Dad were very, very happy. At ages 41, they finally had their much-wanted baby.

In 1948, when I was 3 years old, we took a vacation trip down into West Virginia (don’t ask, because I don’t know, why they chose that state). Motels were just starting to come in then, and the one we stopped at one night wasn’t even finished yet. But the owner’s house was right beside it, and they had a guest room. So they rented it to us for a couple of nights. During the evenings, the owner and Dad sat outside on the porch and talked — about motels. Apparently it planted the germ of an idea in Tony’s mind: To be an independent businessman; to own his own place; not to have to kowtow to a boss any more.

He and Rubye talked it over at length, and I guess her reaction was, “If that’s what you really want to do, let’s go for it!” Or some equivalent saying popular in those days. As her parents lived in Madison, they contacted them to see if there was a lot available in a well-traveled part of town where they could build Tony’s dream: Their own motel.

Grandpa investigated, and found out that, lo and behold, there was a whole corner lot, seven acres, available at the intersection of what was then U.S. 29 and S.R. 107. An elderly couple named Dick and Mattie Keller owned the land, and lived right next door. Overtures were made; Grandpa loaned Tony some money, and Dad borrowed $3,000 more from one of the local banks, on Grandpa’s recommendation. A price was agreed on, and money and the deed changed hands. And in the spring of 1949, Tony, Rubye and their little 4-year-old son moved to Madison in the Engles’ 1937 Chevy two-door.

Becoming “his own boss”

Tony and Rubye wasted no time in getting started on their new motel, which they decided to call the “Englewood Tourist Court.” And yes, you’re right — it’s still in business, as the “Englewood Motel,” in a now-busy commercial area bounded by Michigan Road and Clifty Drive. Dad hired a finish carpenter, and he and that man did the large majority of the building. Mom painted the whole building. I don’t think she had any experience at it, but she did it anyway, and when she was finished you couldn’t tell that a professional house painter hadn’t done it. And Dad, while he never made his living as a carpenter, was a damn good one. And a skilled painter, too. I remember Mom once telling me how well he could paint a window frame without getting any of it on the glass.

They opened the new motel as soon as it was possible to do so. Dad told me once many years later that the place made money, in every year except the first. That year, he worked as a hired hand for a Madison-area farmer named Howard Dahlem to bring in more money to make ends meet, while Mom cleaned the rooms each morning that had been rented the night before. I wasn’t in school yet, so each day I would go with Dad to tag along while he did his farm work. Many mothers probably would have put their foot down on that — “Oh, he’ll get hurt!” I can hear them saying. But Mom didn’t. She trusted Dad, and she had grown up on a farm, too.

After the first year or two, the motel was on a firm enough financial footing that Dad was able to quit his farm hand job. Everything seemed to be going well for the Engles. They joined Trinity United Methodist Church, where Mom sang in the choir for years. She had a beautiful voice, as did several of her sisters. And her oldest brother, Omer, sang country music, and played the guitar, fiddle and mandolin. Music was in the genes of the Wingham family, for sure. On the other hand, Dad couldn’t sing a note — or he claimed he couldn’t. But he loved certain kinds of music. He and Mom were especially fond of Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians. In 1936, the year they moved to Connersville, they traveled to Indianapolis to the state fair that summer, because Lombardo’s orchestra was playing live there.

Rubye’s illnesses, business declines

But then one morning at the motel (I was at school at the time), Mom collapsed in the laundry room, where the sheets, pillow cases, towels, soap, etc., for the motel rooms were kept. Thank God that Dad happened to be right beside her; he caught her, so she didn’t hit the concrete floor. When I came home on the school bus that afternoon, Mom was lying on their bed, fully dressed, with a blanket over her. That was unusual for her, to be lying down during the day. When she looked at me vaguely and said, “Who brought you home?” I knew something was wrong. Even a kid can have instincts, intuition, about what’s going on.

Of course Dad took Mom to the doctor. After numerous tests, his diagnosis was that Mom had suffered an epileptic seizure. Normally if someone is going to be epileptic, they’ll have their first seizure before age 30. Mom was 50. The doctor put her on medication to try to control the epilepsy. But it wasn’t a guarantee that she’d never have another seizure.

In the first year or two, sometimes Rubye would have what doctors call “petite mal” seizures, where she would just freeze in place, often standing, for a minute or two, staring off into space and making funny, nonsensical sounds. Then she’d be over it. But increasingly, she suffered “grand mal” seizures, in which she would go into convulsions, fall helplessly to the ground, bite the inside of her mouth … If you’ve never seen anyone have an epileptic seizure, then count yourself as lucky. It’s a horrible experience for the victim, obviously; and it’s scary and very unsettling to witness.

Rubye was still able to keep house, cook, clean, for the first few years. But her medications and her doctor visits were eating into the small profit the motel was making for her and Tony. Business was slacking off; too. Slowly, things began to fall apart.

Some time in the late 1950s, my folks decided to sell the motel. Tony’s dream hadn’t worked out as they hoped. Sometimes it seemed to me, just entering my teens, that they had been trying to sell it forever. Rubye’s seizures grew worse; she was able to help Tony less in cleaning and maintaining the motel rooms. More and more of the work devolved onto Tony. The folks always insisted that I help with specific tasks involved in re-supplying soap, glasses and towels in the rooms, and carrying the slept-on sheets and pillowcases to the laundry room. But I could have done more. I was lazy, and more interested in my books, and the TV programs, than anything else. There were shouting matches — Mom or Dad vs. me, or them loosing their tempers with each other. I remember that earlier, in happier days, Tony and Rubye had little pet names for each other. Mom was “Suzie.” Dad was “Daddy.” Over time, as life got harder and more gloomy for us, the pet names disappeared.

Selling out, moving downtown

Finally in the spring of 1959, 10 years after they had built Englewood, Tony and Rubye traded it to a Madison couple for their house downtown. The other couple included some “boot money,” as the motel was worth more than the house. Finally out from under the dream that had blown up in their faces, Mom and Dad and their 14-year-old, difficult son moved downtown.

With his 10 years experience with cleaning the motel rooms, Dad was able to get several janitor’s jobs. I think he moved from one place to another occasionally due to being offered more money. He worked slowly, but very thoroughly.

Not too long after we moved to Madison’s downtown, Mom had a stroke. It left her paralyzed on her left side. Her recuperation was slow and painful. Eventually she was able to walk again, but not for very far, and she never could use her left arm again. She still cooked, but had a hard time cleaning or doing laundry. Dad was working as hard as he could to make ends meet, but he pitched in with the home chores, too. He took care of Mom, but he didn’t always do it with a good grace. Dad was not born to be a nursemaid.

Eventually, while I was away in the Army, they had to sell the house. Many years later, after both Tony and Rubye were gone, I found one of Dad’s old record books where he kept track of the family finances. Just before they sold the house, the balance in their joint bank account was 69 cents. That’s right — pennies.

By the time I came home from the service, Mom and Dad were renting part of the big house which was next door to the motel. Both the Kellers, who had been friends of Tony and Rubye, were deceased by then. It was while they were living there that I discovered how much Mom and Dad still meant to each other, despite the arguments and tension that went with Mom’s illnesses and the motel’s failure. The people who had bought the motel occasionally would pay Dad to watch the place for a couple of days so they could take some time off. Once when he was there next door for the weekend, I walked over on Clifty Drive to a sandwich shop which was there then, and bought supper for the three of us. I stopped at the motel to drop off Dad’s meal, and the first thing he said was, “Did you get something for your mother, too?” I said, “Sure, Dad; I’m just taking it over to her now.” When I walked into their apartment next door with Mom’s and my supper, she said, “Did you get something for your dad, too?”

I never told either of them about the questions that each asked. But it made me very happy.

Rubye’s death

A couple of years after that, Mom had another stroke. Now she was totally disabled — able to lie in bed or sit in a chair, but requiring help to walk even a few feet. Dad was working in housekeeping at King’s Daughters’ Hospital by that time. They moved downtown again — I never was sure why — and that house was the last one that either ever lived in.

Tony finally had to hire a woman to stay with Rubye during the day, straining their already-stretched family budget. Finally, Mom got so bad off that he couldn’t afford to keep her at home any more. So he had to have her moved to the Hanover Nursing Center.

Mom was there for about six weeks. Dad and I went to visit her several times. The last time, I noticed that Mom kept gazing lovingly at Dad the whole time we were there. It annoyed me mildly; I was thinking, “Hey, Mom, I’m here, too!” But of course I didn’t say anything. Eventually, he and I left.

A few days later, the Hanover Nursing Center called me one morning at the Madison Courier where I was working then. “Hon, your mom has passed away,” said a nurse in a solicitous voice.

It was a heart attack, sudden. Rubye had no history of heart trouble. I think she had a premonition that our visit a few days earlier was the last time she would see her Tony. In this life, anyway.

Dad and I were devastated, needless to say. For months afterwards, when I would go down for supper with him three times a week, I would catch him staring off sadly into space after we had finished and were watching TV in the living room. But neither on the day of Mom’s death, at her funeral, or any other time after that, did Dad let me see him cry — although I know he did. For a while, I would let him know just what time I would arrive at his house, so he could compose himself, in case he needed to.

Tony’s last years

Dad out-lived Mom by about 13 and a half years. He eventually got through (not “over”) Mom’s death. He and I became closer friends than we had ever been before. We shared a meal three times a week. He told me things about his boyhood that he never had before. I just wish I had insisted, occasionally, that he let me give him some money toward feeding me, as by this time he was living pretty meagerly.

But I’m sure he would have been insulted if I had offered. After all, I was his son. I was always welcome there, and always welcome to break bread.

Dad seemed less inhibited about talking about things after Mom’s death than he had been when she was living. For one thing, when I was growing up, I almost never heard Dad swear. I think he had “orders” from Mom not to use foul language around me. Not that it kept me from learning Billingsgate. I remember saying something in Mom’s presence once that made her so mad she dragged me over to the lavatory, grabbed and lathered up a bar of brown laundry soap, and scrubbed my mouth out with it, saying, “This is what we do to little boys who talk dirty!” It didn’t cure me of swearing; just made me more careful about where I did it.

I learned after Mom’s death that Dad could cuss the hinges off a door, if he chose to. And he also had ways of saying a few things that were — well, “original,” to say the least.

If we were watching a college basketball game (Tony was a big IU-Bobby Knight fan), and some IU player was really scoring heavily, he’d look at me, grin, and say, “He’s the main gazeek!” If the biggest guy on the other team was scoring heavily, he’d frown, and growl, “Damn big lobster!”

To Dad, something very dark in color was “black as Coley’s ass.” Someone who he judged to be mentally unsound was “off his rocket.”

If someone spoke about a debt they owed, Tony would chime in, “Charge it to the dust and let the rain settle it!” If he was paying for something with a personal check, often he’d say, “There you are! Now, if that one’s no good, I’ll write you another just like it!” If he was paying cash for something, he’d say, “Give me my change all in ones, so I’ll think I’ve got a lot of money!”

I’ll always be thankful that the evening Dad had his fatal stroke, about 16 days after his 80th birthday, I happened to be there at his house, so I could call an ambulance and do what I could to help him until they got there. He lived for about two days, then passed away. I don’t think he’d been conscious since late on the evening he had the stroke.

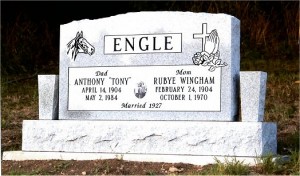

A memorial — finally

Mom and Dad are buried side by side in our main local cemetery here in Madison. For many years, the only marker was a small one abut the size of a loaf of bread, on Mom’s plot. I should have done something about that sooner; I just didn’t. No excuses; my fault. Sorry, Mom and Dad. But two years ago, I finally had a nice monument made for both of them, and put in place. You’ll see a photo of it at the top of this story, along with a photo of Tony and Rubye, taken on their wedding day, in 1927. The praying hands on Mom’s side of the monument are obviously due to her devout Christianity. The race horse on Dad’s side? Well, once he told me about how, when he was a teenager, he would have given anything in the world to be a harness-race jockey — but he never got to. And I have an old photo of him from about the same time period, out in the barn yard, proudly holding the head of a big horse which looks like it could be a racer.

Well, Tony and Rubye — Mom and Dad — here are your life stories, written by the son who loved you, despite all the difficulties and grief he sometimes caused you. Wish you could have read this, while you were alive. But then, who am I to say you can’t, right now? …

7 comments for “Tony and Rubye — my Mom and Dad”