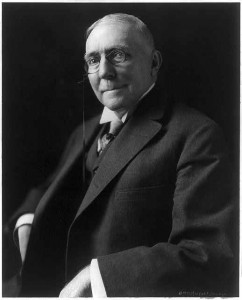

He was as well known as almost any American of his day. From the early 1880s, until his death in 1916, he was a much-sought public speaker, reading his poetry before many thousands of what would be called “fans” nowadays. He was a “rock star” before the term was even coined.

Yet today, many Americans, not to mention many residents of Indiana, have never heard of James Whitcomb Riley, known fondly in his day as “The Hoosier Poet.” Ever hear the phrase, “When the frost is on the punkin”? It is probably the best-known start to any of his poems, written in the Hoosier dialect that made his poetry unique — and yet caused many later “poetry critics” to refuse to take him seriously among a pantheon of rhymsters which included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. Riley wrote, often, in that dialect of the Indiana farm people; therefore, said the poetry “experts,” that made his poetry intended for the “common people;” therefore, his poetry was OK for its time, but not worth remembering alongside “The Wonderful One-Horse Shay” or “The Legend of Hiawatha”, or “Leaves of Grass.” Riley’s work was not high-falutin enough for the intellectual monitors of “true poetry,” so the high-flown sachems of what constituted “great poetry” passed it by on the other side of the road. Sniff.

Last Tuesday, Oct. 7, week ago today, was the 165th anniversary of Riley’s birth, at Greenfield, Indiana, Oct. 7, 1849. His father, Reuben Riley, was an attorney who had been elected to the Indiana General Assembly in 1848, as a Democrat. His mother, Elizabeth Marine Riley, was a a gentle, loving woman who wrote her own poetry occasionally — but who always poo-pooed her own talents, and who, early on in the life of her dreamy, unusual son, told him that he was the family member who had true genius when it came to rhymes.

Fast forward a few years, and we see the Riley family bereft of their beloved mother, who died young, leaving behind besides her husband and Jim, or “Bud” as they called him in childhood, two daughters and a third son, all younger than Jim.

Jim Riley set off to make something of himself in the world — but hating any kind of manual labor, having no interest in history or politics, and being of a somewhat indolent nature. The one thing that interested him intensely, though, was the poetry that he could produce by the bushel basket full — the same kind of basket that the good farmers of Indiana whom he loved and depicted, used in their daily chores.

He began sending copies of his poems to Indiana newspapers, who were happy to print them, as they didn’t have to pay him anything. But it started to get him the recognition that grew and grew until he was famed, and sought after as a reciter of his own works, nationwide.

One of the best known of those poems, to this day, is the one that provided the saying we still use to refer to the late fall and the changes it brings.

When the frost is on the punkin

When the frost is on the punkin and the fodder’s in the shock,

And you hear the kyouck and gobble of the struttin’ turkey-cock,

And the clackin’ of the guineys, and the cluckin’ of the hens,

And the rooster’s hallylooyer as he tiptoes on the fence;

O, it’s then’s the times a feller is a-feelin’ at his best,

With the risin’ sun to greet him from a night of peaceful rest,

As he leaves the house, bareheaded, and goes to feed the stock,

When the frost is on the punkin and the fodder’s in the shock.

They’s something kindo’ harty-like about the atmusfere

When the heat of summer’s over and the coolin’ fall is here–

Of course we miss the flowers, and the blossums on the trees,

And the mumble of the hummin’-birds and buzzin’ of the bees;

But the air’s so appetizin’; and the landscape through the haze

Of a crisp and sunny morning of the airly autumn days

Is a pictur’ that no painter has the colorin’ to mock–

When the frost is on the punkin and the fodder’s in the shock.

The husky, rusty russel of the tossels of the corn,

And the raspin’ of the tangled leaves, as golden as the morn;

The stubble in the furries–kindo’ lonesome-like, but still

A-preachin’ sermons to us of the barns they growed to fill;

The strawsack in the medder, and the reaper in the shed;

The hosses in theyr stalls below–the clover overhead!–

O, it sets my hart a-clickin’ like the tickin’ of a clock,

When the frost is on the punkin, and the fodder’s in the shock!

Then your apples all is gethered, and the ones a feller keeps

Is poured around the celler-floor in red and yeller heaps;

And your cider-makin’s over, and your wimmern-folks is through

With their mince and apple-butter, and theyr souse and saussage, too!

I don’t know how to tell it–but ef sich a thing could be

As the Angels wantin’ boardin’, and they’d call around on me–

I’d want to ‘commodate ’em–all the whole-indurin’ flock–

When the frost is on the punkin and the fodder’s in the shock!

Riley eventually took a job painting signs (he had considerable artistic talent, as well as poetical), while still sending his poetry to the newspapers. Eventually, through contacts with a few friends and the growing celebrity his poems were attracting, he began doing recitations of them before audiences. But at first, his stipend for these appearances was small to non-existent — especially since he often had to ride trains (which he hated) to get to those places.

Jim Riley, the name he still went by, presented an unusual picture to those attending his recitations: a shortish, blondish, blue-eyed, slim young man who tended to dress somewhat outlandishly (in his later, more prosperous years, he wore more conventional garb, and was always faultlessly neat). He was shy by nature, and didn’t like having to do much “speechifying” at the lectern, preferring to simply recite his poems. But once he immersed himself in his favorite pastime, his natural acting talents would kick in (Riley probably approached genius status in some things), and the audience would sit enthralled, laughing at the funny passages, crying at the emotional ones, and recognizing many familiar things about the way they and their neighbors talked, and thought, and lived their lives.

Another poem of Riley’s which audiences loved to hear, “Little Orphant Annie,” was written with a weird little orphan girl named Allie in mind. She had been taken in by the Riley family at the age of 13 or 14, living with them for some months, exhibiting many unusual qualities, such as talking and singing to herself as she worked; and enthralling the Riley children with the tales she would tell them in the evening after the supper dishes were washed and put away. When Riley wrote this poem, the printer who set it in type misread the girl’s name and put it down as “Annie.” And Annie she remains, to this day.

Little Orphant Annie

- Little Orphant Annie’s come to our house to stay,

- An’ wash the cups an’ saucers up, an’ brush the crumbs away,

- An’ shoo the chickens off the porch, an’ dust the hearth, an’ sweep,

- An’ make the fire, an’ bake the bread, an’ earn her board-an’-keep;

- An’ all us other children, when the supper-things is done,

- We set around the kitchen fire an’ has the mostest fun

- A-list’nin’ to the witch-tales ‘at Annie tells about,

- An’ the Gobble-uns ‘at gits you

- Ef you

- Don’t

- Watch

- Out!

- Wunst they wuz a little boy wouldn’t say his prayers,–

- An’ when he went to bed at night, away up-stairs,

- His Mammy heerd him holler, an’ his Daddy heerd him bawl,

- An’ when they turn’t the kivvers down, he wuzn’t there at all!

- An’ they seeked him in the rafter-room, an’ cubby-hole, an’ press,

- An’ seeked him up the chimbly-flue, an’ ever’-wheres, I guess;

- But all they ever found wuz thist his pants an’ roundabout:–

- An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

- Ef you

- Don’t

- Watch

- Out!

- An’ one time a little girl ‘ud allus laugh an’ grin,

- An’ make fun of ever’ one, an’ all her blood-an’-kin;

- An’ wunst, when they was “company,” an’ ole folks wuz there,

- She mocked ’em an’ shocked ’em, an’ said she didn’t care!

- An’ thist as she kicked her heels, an’ turn’t to run an’ hide,

- They wuz two great big Black Things a-standin’ by her side,

- An’ they snatched her through the ceilin’ ‘fore she knowed what she’s about!

- An’ the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

- Ef you

- Don’t

- Watch

- Out!

- An’ little Orphant Annie says, when the blaze is blue,

- An’ the lamp-wick sputters, an’ the wind goes woo-oo!

- An’ you hear the crickets quit, an’ the moon is gray,

- An’ the lightnin’-bugs in dew is all squenched away,–

- You better mind yer parunts, an’ yer teachurs fond an’ dear,

- An’ churish them ‘at loves you, an’ dry the orphant’s tear,

- An’ he’p the pore an’ needy ones ‘at clusters all about,

- Er the Gobble-uns ‘ll git you

- Ef you

- Don’t

- Watch

- Out!

From the late 1870s, into the 1880s, Riley’s fame continued to spread, and his pocketbook became weightier as he eventually learned to charge a good price for his appearances. Various aspects of his adult character began to come more into focus, too. He was a man who never managed to marry or father children — but research indicates he had a number of brief romances with various women. He was a pleasant man who had many friends, including Mark Twain (their relationship was always a little strained, though); Gen. Lew Wallace, a fellow Hoosier who wrote the epic novel “Ben-Hur;” and President Benjamin Harrison, who lived most of his life in Indiana. But Riley did not like overt familiarity, such as slaps on the back or too-casual addressing by strangers on the street.

And from his teen years on, Jim Riley had a weakness for alcohol. His occasional binges sometimes caused him embarrassment, and even interfered with his poetry readings. I can remember my mother telling me when I was a child how she had read that once he and Mark Twain were both scheduled to do readings at a major city, but that there were several hours to kill before the program. Fearing that Riley would “get on a toot” in that length of time, Twain contrived to lock him in Riley’s hotel room, without any liquor, thinking that at least then he would be sober to recite. Alas, Twain had failed to consider the extreme inventiveness of a near-genius alcoholic with a thirst upon him. Riley managed to get the attention of a bellhop who was passing down the hall, slid some money under the door, and asked the man to come back with a bottle of whiskey and a drinking straw. No sooner said than done — Riley had included a generous tip in the cash. When he returned, the bellhop had to stand just outside the door, holding the bottle and terrified that someone would come along and catch him, while Riley used the straw to slurp up the whiskey through the keyhole. The bottle finally empty, the bellhop beat a hasty retreat, and when Twain returned to release his friend to accompany him to the recital, he found him, as an uncle of mine used to say, “Drunker than seven hundred dollars.” Riley was unable to go on that evening, as you may have guessed.

But despite his alcoholism, James Whitcomb Riley (he had begun using his full name on the title pages of books of his poetry — it was more distinctive than “Jim Riley,” after all) continued to travel, and speak to adoring crowds. His fees mounted, and were gladly paid by his hosts, who came out well themselves because of the heavy demand for tickets for the shows.

Living in Indianapolis as the 20th Century dawned, able to afford servants to take care of his comfortable home, Riley didn’t write many poems in his later years. His followers loved to hear the old ones so well, and he didn’t need the extra income that publishing books of new poetry might have brought him. In 1910 he suffered a stroke which left his right side paralyzed (and he was right-handed, and so could not write for himself any longer). It depressed him greatly, and led to more heavy drinking. He did agree in 1912 to allow recordings to be made of his voice, reciting some of his best-known poems — such as the one just below.

The Old Swimmin’ Hole

Oh! the old swimmin’-hole! whare the crick so still and deep

Looked like a baby-river that was laying half asleep,

And the gurgle of the worter round the drift jest below

Sounded like the laugh of something we onc’t ust to know

Before we could remember anything but the eyes

Of the angels lookin’ out as we left Paradise;

But the merry days of youth is beyond our controle,

And it’s hard to part ferever with the old swimmin’-hole.

Oh! the old swimmin’-hole! In the happy days of yore,

When I ust to lean above it on the old sickamore,

Oh! it showed me a face in its warm sunny tide

That gazed back at me so gay and glorified,

It made me love myself, as I leaped to caress

My shadder smilin’ up at me with sich tenderness.

But them days is past and gone, and old Time’s tuck his toll

From the old man come back to the old swimmin’-hole.

Oh! the old swimmin’-hole! In the long, lazy days

When the humdrum of school made so many run-a-ways,

How plesant was the jurney down the old dusty lane,

Whare the tracks of our bare feet was all printed so plane

You could tell by the dent of the heel and the sole

They was lots o’ fun on hands at the old swimmin’-hole.

But the lost joys is past! Let your tears in sorrow roll

Like the rain that ust to dapple up the old swimmin’-hole.

Thare the bullrushes growed, and the cattails so tall,

And the sunshine and shadder fell over it all;

And it mottled the worter with amber and gold

Tel the glad lilies rocked in the ripples that rolled;

And the snake-feeder’s four gauzy wings fluttered by

Like the ghost of a daisy dropped out of the sky,

Or a wownded apple-blossom in the breeze’s controle

As it cut acrost some orchard to’rds the old swimmin’-hole.

Oh! the old swimmin’-hole! When I last saw the place,

The scenes was all changed, like the change in my face;

The bridge of the railroad now crosses the spot

Whare the old divin’-log lays sunk and fergot.

And I stray down the banks whare the trees ust to be —

But never again will theyr shade shelter me!

And I wish in my sorrow I could strip to the soul,

And dive off in my grave like the old swimmin’-hole.

The illustration on the cover of the book of James Whitcomb Riley’s poetry for children, shown above, depicts the “old swimmin’ hole” described in the poem. Since 1912, the book has never been out of print. Millions of copies have been sold. Mom bought one of them for me before I could even read. I grew up with James Whitcomb Riley and his fascinating, humorous, touching poems about the Hoosiers of his early life.

Late in James Whitcomb Riley’s life, the Indiana state government designated his birthday as “Riley Day” in Indiana, with requirements that his poetry be read in all public schools in the state on that day. Many other states followed suit.

On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered his second stroke; later that day, he died, age 66. He had fought bad health periodically all his life. The nation mourned him. He may have been the “Hoosier Poet,” but he belonged to America.

It is sad that, in this day and age, 98 years after his death, he seems to have been widely forgotten. I hope this essay will help re-introduce him to a new generation of his beloved Hoosiers — and to all other Americans, as well.

1 comment for “Have we forgotten “The Hoosier Poet”?”