EMMETT

EMMETT

Listened to any Emmett Miller records lately? No? Don’t feel lonely. He was a giant American musical influence of the 20th Century who is almost unknown today.

Emmett Miller sounds like it could be the name of a guy who lives down the street; graduated from MCHS; worked a career at the IKEC plant; retired now; good family man. Such a typically American-sounding name for a guy who influenced two generations of (mostly country) singers.

Miller was born in Macon, Ga., Feb. 2, 1900. He was one of five children of a working-class white family. Even as a child, he was fascinated by the speech and music of the black people who also lived in his town, spending many hours in the black neighborhood, listening and learning. One of his (white) childhood friends said many years later, “He got so he talked just like a black man.”

He also was a very gifted natural singer, who as a young man went into the minstrel show branch of the entertainment business. For those of you too young to remember, minstrel was a stage show combining music, dance and comedy. It’s frowned on today as “racist,” since the “end men” on the minstrel line stretching across the stage were always white men wearing blackface makeup and pretending to be black, down to talking and singing in an exaggerated African American dialect, or possibly what white people perceived to be such. That was Emmett Miller. He didn’t have to “learn” to talk or vocalize that way; he’d already learned as a child. His natural talent for singing and comedy did the rest.

Miller’s fame as a minstrel man spread until during the mid-1920s, he was signed to make some phonograph records — most for the Okeh label. In one series of records cut in 1928-29 he had some back-up musicians you may have heard of at some time or another: On clarinet and alto sax, Jimmy Dorsey; on trombone, Tommy Dorsey; Gene Krupa on drums; and Eddie Lang as guitarist. As a group, they were referred to on these records as the Georgia Crackers.

Some of the songs recorded in that series may ring a bell for you, too: “I Aint’t Got Nobody;” “Lovesick Blues;” “Any Time;” “St. Louis Blues;” and “You’re the Cream in My Coffee.”

Miller’s singing style, in a relaxed, mellifluous tenor that sounded like a middle-aged black man, featured a frequent break, or catch, in his voice that was a first cousin to Swiss yodeling, and gave his singing a very unique sound — little like what we would call country music today, but more a jazzy, Dixieland lilt. Within a year or two of Miller’s first recordings, a former railroad brakeman named Jimmie Rodgers was singing in a similar style that led to the selling of millions of his own records. Miller is believed to have been a major influence on Rodgers’ style, which is considered the precursor of that of most of the country music singers who have come after.

Note also that one of his songs in this series of records was titled “Lovesick Blues.” Twenty-odd years later, it was the first big hit recorded by a country music legend called Hank Williams Sr.

This is what Hank Williams Jr. had to say about “Lovesick Blues:” “Without a doubt my father learned ‘The Lovesick Blues’ some time from Emmett Miller. It was either by record or he heard him perform it in person at a minstrel show.”

With all his superb talent, Emmett Miller was unable or unwilling to change with the times. Minstrel was already starting to be superseded by “hillbilly singing” (on records) and by music in sound movies by the time he reached his 30th birthday. There are a few film clips existing that show Miller singing or doing his “blackface” comedy. You can watch them on YouTube under “Lovesick Blues” or MySpace under “Emmett Miller.” Be warned: Miller wears blackface makeup and talks in black “dialect” in these clips; if such things offend you, perhaps you’d better not watch them.

Miller’s recording career ended by the mid-30s; his minstrel days were over a few years after that. He married, for the first and only time, in 1943; the marriage didn’t last long.

As a young man, photos of Miller (without his blackface makeup) show a pleasant-enough looking fellow, not matinee-idol handsome but not ugly either. Average; just like his name. Apparently his uniqueness didn’t become apparent until he started to sing.

A photo taken in 1949, when he was 49 years old, depicts a puffy-looking guy in suit, tie and fedora, looking a good 10 years older than his real age. Miller was reportedly a heavy drinker. He returned to his hometown of Macon some time during the 1950s, and little more is known about him until his death on March 29, 1962, of cancer of the esophagus, which is often related to heavy consumption of alcohol.

Most Americans knew nothing of the existence of Miller until Nick Tosches included a section on his life and influence on American music in his book “Dead Voices Gather” (2002).

But professional musicians knew of him. Leon Redbone considers Miller a major influence on his career. Redbone wrote an article about Miller for a French magazine in 1991. In part, he said of the musical Georgian: “I would like to think that the world has heart enough to remember Emmett Miller as a catalyst for the music that came after him and because of him. I personally thank him for the hours of inspiration and good humor which his recordings have given me.”

Of one of Miller’s songs, Ray Benson of the band Asleep At The Wheel wrote: “…Here was a record by a man, largely unknown to most modern-day musicians and singers, who was one of the original architects of modern country and popular music.”

Miller is also considered to have been a major influence on Bob Wills, creator of Western Swing; and country music legend Eddy Arnold (“Any Time” was considered Arnold’s theme song.)

Nick Tosches deserves the last, most profound word: “The music of Emmett Miller — or call it magic or call it mystery — is as wondrous today as it was when he wrought it, a world ago. Emanation and transcendence of the bloodlines of country and blues, jazz and pop, black and white, it stands unique: prophecy and summation, birth-cry and howl everlasting of the chimera of all that has come to be known as American music.”

——

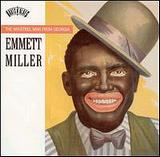

The only collection of Miller’s music that I’m aware of being available on CD is called “Emmett Miller — The Minstrel Man From Georgia.” It used to be for sale on Amazon, but recently the giant company put a notice on the web page for Miller’s CD saying that it had been discontinued by its manufacturer. Try googling his name; you may get lucky.

——

One personal note: I was privileged to attend the last minstrel show ever held in Madison, in about 1954, at the old Madison Theater, on the corner of the alley in what is now the Main Street parking lot, Main and Poplar. It was a unique experience, not like anything you’d ever see on TV or in a movie made since that decade. The music was provided by a five-piece dance band called the Madisonians, headed by my high school band director, Harold Rothert. No doubt some of you remember “Doc Rothert,” a great musician who knew the immortal Hoagy Carmichael when both were students at Indiana University.

Old Corporal <corporalko@yahoo.com>

1 comment for “Emmett Miller”