Paul Rhodes was a very smart guy. Too smart to believe in all that nonsense about an “invisible man in the sky,” or “life after death,” or “heaven and hell.” Oh, yeah; he was too smart for all that fairy tale stuff. Don’t believe me? Why, for a long time, you could just ask him, and he’d tell you how right I am.

Paul Rhodes was a very smart guy. Too smart to believe in all that nonsense about an “invisible man in the sky,” or “life after death,” or “heaven and hell.” Oh, yeah; he was too smart for all that fairy tale stuff. Don’t believe me? Why, for a long time, you could just ask him, and he’d tell you how right I am.

Both of Paul’s parents were atheists, see. They were college professors. Loved to ridicule any of their students who expressed a belief in those things they insisted were “myths,” concocted for “simple-minded, sheep-like people who aren’t smart enough or sure enough of themselves to make their own way in the world.” Not among the Mensa-class elite, like them. So, growing up, Paul absorbed all that from his folks. They would have said that another little boy, who was taught about the Bible (or the Talmud, or the Koran), and taken to worship by his parents, was being “brainwashed” to become “one of the sheeple.” But their little Paul was being “taught about the real world,” and shown how to avoid “playing a sucker to some religious cult like all those stupid people out there.” Stupid people; not “smart people,” like them.

Little Paul thus learned to regard himself as an intellectual among dunces. The Rhodeses had taught their son from toddlerhood that there was “no Santa Claus,” and he took particular glee in announcing this fact to his little friends at Christmastime, and to spiking any attempt they might make to argue otherwise.

“Prove it!” he’d say, laughing in their faces. “You can’t, can you? Because it isn’t true. There’s no Santa Claus, no reindeer, no toy factory up there at the North Pole! That’s a fairy tale, and you fell for it! You’re SUCKERS! Your folks buy all those presents, and put ’em under the tree, after you go to bed Christmas Eve. You really think some guy could fly all over the world, in one night, in a magic SLEIGH? And slide down millions of chimneys — even in houses that are lit with electric heat? And carry enough toys for millions of children, in one big old sack? HA! They’ll have you convinced the moon is made of green cheese, next!”

NEEDLESS TO SAY, all that pontificating didn’t make little Paul real popular with his friends, some of whom he taunted until they were crying. Or with their parents, when the kids told them about his harangues. But Paul didn’t care; he was SMART! He wasn’t a sucker like these “common” kids who believed everything they were told.

As little Paul grew up into teenage Paul, then young adult Paul, his ridiculing switched from Santa Claus, to religion in general, and Christianity in particular.

“So you think some imaginary ‘man in the sky’ created this whole world, and is up there looking down on you 24/7? HA! Prove it! Prove there’s a god! You can’t, because there isn’t any! How can intelligent people believe all that crap?! Look at all these huge, costly churches! Think how many poor, hungry children could have been fed with all the millions that were wasted on those fairy tale factories!”

Paul became unpopular at frat parties, and later at office Christmas parties, with his ranting. Oh, he talked about other things, too; like what a great man Nelson Mandela was, and how all those people who didn’t like President Obama were racists, and how millionaires should be taxed at about 90 percent so that their money could be re-distributed to the “poor and hungry.” Scratch an atheist, find a liberal.

But Paul didn’t really care about popularity. He was smart, and he became a lawyer in a big firm, and his opinion of himself swelled to Brobdingnagian proportions. Being tall and handsome helped his self-esteem, also.

HIS FAVORITE PERSON had always been himself — until he met Julie Vronsky, a new receptionist at the office. She was sweet-faced, averaged-sized, and with a personality so gentle and loving that it turned Paul into putty in her hands — well, to a degree, anyway. They hadn’t gone out together very many times before Paul popped the question to Julie — to which she gladly said “yes,” because she saw him as her Sir Galahad, her knight in shining armor.

Here’s an ironic fact, though: Julie was a devout Orthodox Christian, who still attended Divine Liturgy at St. Vladimir’s Russian Orthodox Church each Sunday with her parents. Arrogant, cocky Paul Rhodes had fallen in love with one of those “simple-minded, sheeplike people” his parents had warned him about!

But Paul didn’t care. Julie was who he wanted, and he was willing to bend a little to gain her hand.

But her parents weren’t happy about their daughter’s choice of fiances, when they heard a few things about his beliefs.

“Honey, don’t you realize it was to escape from cynical disbelievers like him that your grandparents fled the Soviet Union?” her mother asked her one day as Julie was helping her prepare dinner. “Do you know what a hell the communists made for Christians like us, in the old country?”

“MOM, THAT WAS then; this is now. Paul is a good, hard-working attorney who loves me very much — just as I love him. I think you’ll discover that he’ll make you and Dad a fine son-in-law,” Julie declared, in respectful but determined tones. “And he’s NOT a communist!”

Finally her parents agreed to give the marriage their blessing. But they insisted on a full-scale, Orthodox church wedding — no judge or justice of the peace was going to pronounce the marriage rites for THEIR little girl! It would be Father Kosanovich, or no one.

Paul wasn’t happy with the ultimatum, given his views on any kind of religion. His mother had died while he was in college, but his father was distressed about a wedding for his “brilliant” son in the huge, ornate church, surrounded by people he believed to be morons who believed in fairy tales.

“If you could only be wed in a civil ceremony, with my friend Judge Weinstein officiating,” lamented the elder Rhodes. “Not some mumbo-jumbo nonsense in one of those huge churches, where millions of dollars were wasted that could have fed hungry children!”

“Dad, I know how you feel; and you know I agree with you,” Paul said. “But Julie won’t buck her parents on this, and if we want the marriage to go forward, it’s going to have to be in the church.”

SO, FINALLY AND reluctantly, Mr. Rhodes Sr. gave his consent, too. The wedding took place amid much fanfare, with many friends in attendance, and the bride and groom looking like Prince Charming and Cinderella, especially when the symbolic crowns were held over their heads to indicate they were “king and queen” of the day, which is a custom at Orthodox weddings. Rhodes Sr. was seen to roll his eyes at that; he thought royalty was nonsense, too.

But the Vronskys were delighted, and Paul hid any discomfort he felt at the religious surroundings for Julie’s sake. For he truly did love his blushing bride.

They bought a townhouse (Paul had done well already in his law practice, so they felt they could afford it), furnished it in good taste, and began their married life. Julie insisted on having an “icon corner” in their new townhouse. They’re traditional centers of worship in Orthodox homes. Paul went along with it to keep her happy, but insisted that the corner be placed such that he wouldn’t have to see it very often. And so they learned to compromise.

About a year later, Julie gave birth to a beautiful little daughter, whom they named Anastasia (for Julie’s Russian ancestry) Irene (in memory of Paul’s mother, for that was her name). But she quickly became “Tasia,” to everyone.

Paul was sorry that Tasia never would get to meet his mother. He had been close to her, and missed her very much. He had a small photo of her with him, when he was only a toddler, that he was very fond of. Paul saw a pocket watch for sale one day at a shop, and on a whim, he bought it. When he brought it home, and opened the case, he realized that his little photo of himself and his mom would fit inside the case, with a little careful trimming around the edges to make it round. So he trimmed, and crazy glued it into the side of the case opposite the face, where it fit as if the watch had been designed just for it. From that day forward, he carried the watch on a chain in his pocket (although he wore a regular wristwatch, too.) When Tasia was old enough to understand things, he showed her the watch with the photo of her grandma and her daddy, and she was fascinated by it. Talking by this time, she would tug on his sleeve or his coat and say, “Daddy, me see Grammy watch?” And of course he would pull it out so she could look at it and the photo to her heart’s content.

ONE DAY, WHEN Paul was conducting an interview with a client in a room just off the courtroom, the lawyer excused himself to go to the bathroom. He pulled the watch out and looked at it just as he went in, then dropped it back into his pocket. He finished in the bathroom, washed his hands and returned to his interview.

Paul arrived home that day at about 5 o’clock, his usual time, kissed Julie, dangled Tasia in the air over his head (she loved it when he did that), then sat down at his computer to do a little surfing before supper. Before he long a felt a tug at his sleeve, and his baby’s little voice saying, “Daddy, me see Grammy watch?”

“Sure, honey,” he said, patting her shoulder. He reached into his pocket — and froze. The watch was gone. No watch; no chain. He quickly checked the belt loop he always attached the chain to. The loop was intact; no, it hadn’t ripped loose. Paul searched the whole house desperately. Running out to his car, he ransacked it, but found no trace of the watch — and, what was much more important, the old photo of his mother and his young self. It was the only copy he had of that particular picture, and it was his favorite of his mom.

Paul returned to the house, feeling a sense of tremendous loss. He told Julie what had happened, and she helped him look. Little Tasia watched them, puzzled, asking a couple of times, “Daddy, Grammy watch?”

Finally he gave up the search at home, sank into his armchair, placed his elbows on his knees and buried his face in his hands. “Julie, I must have been an idiot to carry that picture around with me, as precious as it was to me, with no second copy of it!” he said, close to tears.

HIS WIFE KNELT down beside him, embraced him. “Honey, don’t get all down, now; we’ll find it. We’ll find it!”

They searched the house — again. The next day, they both retraced Paul’s steps of the day before — especially when he re-entered the courthouse bathroom and looked everywhere — for that’s the last time he’d known for sure he had the watch. But — nothing. Not a trace.

Little Tasia that night said plaintively, “Daddy, Grammy watch?” Feeling like the worst father in the world, Paul took her on his lap and tried to explain to her that he had misplaced the Grammy watch, and was still trying to find it. She began crying. “Me want Grammy watch!” Julie sat down beside her husband and daughter, embracing her and saying softly, “Darling, Daddy feels terrible that he can’t show you the watch you love so much! We’re both trying to find it. OK? Here — here’s your Raggedy Ann dollie. Now come into the kitchen with me and I’ll give you a yummy treat.”

But the watch was gone — gone like the dodo bird or the passenger pigeon. Paul gradually became reconciled to it, although he remained heartsick, deep down, at his loss. Julie tried to console him, and gradually his normal, rather arrogant personality began to emerge again. After all, he was a very smart guy — too smart to believe in sentimental nonsense. Wasn’t he?

Several years passed. Tasia grew, gradually forgot the “grammy watch,” entered pre-school, then kindergarten, and finally first grade. She grew tall, like her dad; and pretty, like her mom, with long brownish-blonde hair and soulful blue eyes.

TASIA DEFINITELY LEANED to her mom’s side of the family when it came to faith. She eagerly attended church with Julie each Sunday. Paul would drop them off at St. Vladimir’s, then head to a restaurant in the suburbs for a doughnut, coffee and the Sunday paper until it was about time for Divine Liturgy to end. He would then pick them up at the church after the “social hour” which always followed the service. Paul wouldn’t set foot in the church. He always felt that he had violated his non-belief enough by agreeing to a church wedding. Occasionally he and Julie would get into arguments — well, friendly disagreements, actually — about the twin issues of religion and atheism. When they did, Tasia would stand a little way off, looking uneasy to hear her parents debate what she was growing to know would be the future direction of her life.

But for the most part, their home life was loving and happy. Paul and Julie managed to keep their disagreements about religion out of discussions — most of the time — and Tasia was proving a bright student who got along well with her classmates in school.

Then, in the summer just after her 8th birthday, a cloud suddenly hid the sun of their lives. Tasia’s energy level began to sag, she started having stomach pains and diarrhea, then her appetite dropped precipitously. A thorough check-up by their family doctor led to additional tests, then the terrible news: Tasia had cancer, near her stomach, and she would have to begin immediate chemo and radiation treatments.

It struck them like a bolt from the blue. When Paul and Julie tried to explain the situation to Tasia, she got a terrified look in her blue eyes, and cried with alarm, “Mommy! Daddy! Am I gonna die?!” Her parents tried to explain to her that the treatments were meant to assure she WOULDN’T die, but she was inconsolable. Weeping bitter tears, she sobbed, “No! I don’t want to die! I’m just a little kid! I don’t want to leave you guys, and my friends, and Grandpa and Grandma Vronsky! No, no, no!!!” Her parents enveloped her in their arms, and of course, they cried, too. Because they didn’t really know. They might lose their precious little girl, and Christmas was coming on …

The chemo caused Tasia’s long, pretty hair to all fall out. She was totally humiliated, and insisted on wearing a cap to school and everywhere else. It made her nauseous and killed her appetite. During a crying spell one afternoon, she told her mother, “Mommy, maybe it would be better if I just died!” Julie, aghast at the words, held her little girl and tried her best to comfort and encourage her.

JULIE OFFERED PRAYERS each day at the icon corner in their house. Of course, Paul was also worried sick about his little daughter’s illness, but he would have no part of the prayers. “It all has to do with her treatments, honey, and if they work. There’s no imaginary ‘man in the sky.’ ”

“Do you have to keep harping on that?” Julie screamed. “You don’t believe in anything you can’t see, touch or spit on, do you? It sure wouldn’t HURT anything for you try praying, for the first time in your life, for your little girl to live, now would it?”

Paul stormed out of the house, into the garage — and burst into tears. He was being so, so torn by what his parents had taught him from the cradle on up, and his desire for something, ANYTHING, to save little Tasia.

As Christmas Day came closer, Paul and Julie talked about what they were going to get for Tasia — excuse me, what SANTA was going to bring Tasia. She loved her dolls, and they decided that her biggest gift would be a dollhouse — but not just any dollhouse. It was going to be big enough for her to go into, carrying her dolls. It could be snugged into a corner of the living room, they decided. Under the circumstances, Julie said, it WOULD be put in the living room, no matter how they had to do it.

They checked with friends, studied the want ads in the newspaper, and finally hired a carpenter they had been told was first-rate and reasonable. He was to build the dollhouse in the garage, with the door kept securely locked so that Tasia wouldn’t get in there and accidentally see it before Christmas.

THE CARPENTER — a tall, lanky young guy with a ponytail, an ear ring and a tattoo — worked 8 to 5, so that Paul didn’t see him for the first several days. When Paul got home from the office two days before Christmas, Julie was in the kitchen fixing supper. After the usual greetings, she said, “Hon, why don’t you go out and introduce yourself to the carpenter? He said he’ll probably have the house finished before he leaves today, and I’m sure you’d like to see it.”

“Yeah, I would,” Paul said, popping open a can of beer and taking a swig. But first, he walked upstairs to Tasia’s bedroom, knocked gently, and entered. She was in bed, taking the afternoon nap that had become necessary since her illness set in. She woke up, said, “Hi, Daddy,” and extended her arms for her hug.

“How are you feeling, little one?” Paul asked. “Oh, not too bad; just tired,” she answered. “Just hanging on.”

Paul frowned, caressed her face with his hand, and said, “Listen, honey, you’re not ‘hanging on.’ You’re going to lick this illness — WE’RE going to lick it, your mom, you and me. You keep that in your mind. And remember, Christmas Eve is tomorrow. I’ll bet Santa has something really special for you!”

“I thought you told me once there wasn’t any Santa Claus?” she said, looking up at him doubtfully.

“WELL … WELL, just forget that for now,” he said, hoist on his own petard. “For you, this Christmas, there IS a Santa, and he’s coming to see you!”

Paul kissed his little girl on the forehead and walked out, shutting the door gently behind him. Despite his brave words, he did not feel optimistic about her chances.

Going into the garage, he saw the hippie-looking young man putting the final touches to a beautiful little dollhouse. It had an ornate exterior design, old-fashioned windows and doors, chimneys that went from bottom to top of the house on each end as if there were fireplaces in two different rooms; and it was painted in beautiful red, green and white colors — perfect for Christmas for a little girl.

“Wow! That’s a stupendous job you did on that,” said Paul. He extended his hand, saying, “I’m Paul Rhodes, Tasia’s father.”

“Pleased to meet you, mister,” said the young carpenter, grasping his hand in a vice grip. He smiled, showing sturdy white teeth. His eyes held Paul’s, kind but probing, searching …

“HOPE YOUR LITTLE girl really likes this,” he said. “Best one I’ve ever done, if I do say so myself.”

“Yes. I hope she gets to play with it for a while …” Paul began. Then he began to sob. “I’m sorry, fellow; my little girl’s very sick. Her mother and I are afraid — we’re afraid she won’t …”

“Don’t you have faith that God will allow her to live, Mr. Rhodes?” said the man, coming closer, his eyes not moving from Paul’s.

“Faith?” Paul said, gaining control of himself, wiping his eyes with his handkerchief. “I don’t mean to offend you, but I don’t believe in ‘faith.’ That’s all a fairy tale. She’ll live if the doctors can manage to cure that cancer. Period.”

The young man’s eyes continued to search Paul’s. “And what would it take for you to start to believe, my good friend?” he asked softly.

“A HELLUVA MIRACLE,” Paul said without thinking. Then he added hastily, “But that’s not going to happen, because there is no such thing as a miracle.”

Increasingly uncomfortable, Paul got out his wallet, paid the man for his work, and started out of the garage. “Merry Christmas, Mister,” the young man said.

“Yeah,” thought Paul bitterly. “Fine ‘Merry Christmas’ under the circumstances.”

He re-entered the kitchen, where Julie was still preparing dinner. “It’s going to be a little while. Did you meet the carpenter?”

“Yeah,” Paul sighed, sitting down at the table. “He did a beautiful job with the dollhouse. Little strange, though. The guy, I mean.”

JULIE LOOKED AROUND at him. “Strange? Oh, you guys must have somehow gotten onto the subject of religion. He came in here a few times the last few days to use the bathroom or get a drink of water, and when we chatted it came out that I was a practicing Orthodox and you were an atheist. He seemed to find that interesting. How was Tasia when you talked to her up in her room?”

“Oh, she said she felt fairly well; said something about ‘just hanging on.’ That upset me; I told her we were going to lick this thing together. Wish I was as sure of that as I tried to sound.”

Both parents looked up then suddenly; they thought they had heard Tasia’s door open and close, quietly. But she didn’t appear, so they decided they were hearing things.

It took Julia longer than usual to get dinner ready, so it was almost an hour later when she finally said, “OK, hon, you can go up and get Tasia.”

Paul went upstairs, knocked on her door, heard a clear, “Come in, Daddy,” and entered. He glanced at the bed — but she wasn’t in it.

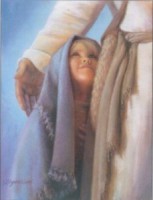

THEN HE REALIZED that his daughter was standing right in front of him, gazing at him lovingly. And then — he noticed that her color was clear and healthy again, as it had been before she got sick. The weight she had lost was back on her slender frame. And her hair — HER HAIR! It was back on her head again, brown and blonde, long and thick!

Paul was so stunned he thought for a moment he would pass out. Tasia walked toward him, put her arms around him, and said, “Daddy, daddy, I think I’m all well again! I think that awful thing is gone!”

Again, Paul broke down and wept, this time for joy, taking his little girl in his arms and hugging her close, kissing her, picking her up and carrying her down the stairs to reveal the wonderful news to her mom.

Julie was surprised and joyful, too of course, holding her “baby” close for long moments, studying her again-healthy face, stroking her hair which was now back, more gorgeous and thick than ever.

But Paul noticed that Julie didn’t seem quite as surprised as he had been.

FOR THE MOMENT, the Rhodes dinner was forgotten. The three sat on the couch in the living room, with both parents embracing their precious child, and she told them what had happened.

“I was asleep after Daddy left my room. After a while, I felt someone sit down on the bed and it woke me up. I looked up, and it was this carpenter guy who’s been here working on something in the garage. I was a little scared at first, with him right in my bedroom, but his eyes were so, so kind, and he talked to me so nice. He told me he knew I’d been sick, but that I shouldn’t worry about it; that I should just get some more sleep, and everything would be all right. He put his hands on my head, where all the hair had come out, and kind of stroked and massaged it, real gently. He kept looking at me with those kind eyes, and he said something like, ‘Go to sleep again, my child, and when you wake, this will all be better.’ And I finally dozed off again. When I woke up, the man was gone. And I felt all better. And I had my hair again! And I don’t know how it happened, but I’m so grateful … Oh, and I almost forgot.” She reached into the pocket of her pajama top and said, “He left this behind on the nightstand.” She held the object up for Paul and Julie to see.

His watch. The watch with the precious photo of his mom and himself, that he had lost years ago, and that he was sure he would never see again. And now he had it back.

Finally drained by their emotional session, the Rhodeses all suddenly realized that they were ravenously hungry. They hurried back to the kitchen and a cold dinner (not that they cared a fig about that, under the circumstances). Paul glanced at the kitchen table, and started again: Because there was a note there. It was written in an old-fashioned, ornate hand. And it said, “Does this qualify as a miracle, my good friend? NOW do you believe?”

At the Christmas Day service at St. Vladimir’s, the parishioners were stunned to see Paul Rhodes come in with his wife and daughter, looking a little sheepish and unsure of himself, but clearly there because he wanted to be.

THEY WERE ALSO startled to see Tasia looking back in good health, with her beautiful long hair again flowing past her shoulders.

After Divine Liturgy, when the congregation was filing out and shaking hands with Father Kosanovich, the pastor grasped Paul Rhodes’ hand, looked at him steadily in the eyes, and said, “Well, Paul, to say seeing you here was a shock would be the understatement of the year. But a very pleasant shock! Tell me, what brings you to God’s house?”

He looked at Paul and saw a man who had been humbled, but enlightened, and who now had a light shining from his eyes. And Paul said, “Well, Father, I guess you could say I was on the road to Damascus, and something happened. Somebody finally proved it.”

2 comments for “From the carpenter’s hands …”