New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie made an interesting statement the other day. He said that if America goes further down the “entitlement route” than we’ve already gone, we’ll no longer be a nation which honors people’s striving for success. We’ll just be, Christie said, “Sitting on the couch, waiting for the welfare check to come.”

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie made an interesting statement the other day. He said that if America goes further down the “entitlement route” than we’ve already gone, we’ll no longer be a nation which honors people’s striving for success. We’ll just be, Christie said, “Sitting on the couch, waiting for the welfare check to come.”

Easy to dismiss such a statement with bromides about being “insensitive” and not caring about “those less fortunate than ourselves.” But he definitely has a point. People of my generation are often appalled nowadays when we see how clueless and lacking in initiative so many young Americans are. It’s the “We’re entitled” generation — or so it appears to us.

Rising by your own initiative and efforts, climbing as high as they would enable you to — those were some of the most distinctive qualities of Americans, dating back to colonial days. We were not a nation of rigid social barriers. This year’s little boy from a poverty-stricken family, might become, in 30 years or so, a multi-millionaire, by inventing a better mousetrap, founding a string of hotels that travelers liked better than the other guy’s, or getting in on the ground floor of a new industry or way of looking at things that was just a-borning.

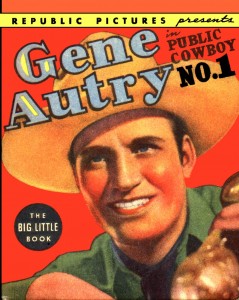

Who was a prime example of that within the living memory of most of us? Why none other than Gene Autry, the original Singing Cowboy.

Oh, sure, I could have found a different example, but in my opinion, not a better one. Besides, he was — is — my childhood hero.

Orvon Grover Autry — his real name — was born on Sept. 29, 1907, in Tioga, Texas, to Delbert and Elnora Ozment Autry. His father was a horse farmer and trader, a charming but feckless man who was casual about providing for his wife and four children, and would sometimes drift off and disappear for weeks at a time, shacked up with some sweet young thing he had met at a tavern. Elnora, Orvon and his two sisters and one brother often suffered grinding poverty, having to depend on other family members for food when Delbert disappeared or came home from horse trading with nothing in his pockets but lint.

But Orvon was one of those Americans who had a drive, an inner desire, which told him, “You’re not going to live out your life struggling on this damn farm. You’re going to AMOUNT to something! People are going to know YOUR name!” He was a workin’ young fool, whether it was in pitching hay on his uncle’s farm, shining shoes in a local barber shop (and entertaining customers with his chief natural attribute, a strikingly good singing voice), or spending a summer with a traveling medicine show when in his teens. Young Orvon got a job punching a telegraph key for the railroad, dropping out of high school short of graduation to pursue it — and always, always, sang and played his $8 guitar at any and every opportunity, when there was someone to hear him, and when there was no one there but him and the ghosts of the railroad station.

Young Orvon watched for his opportunities, rode his railroad pass to New York City to try to get his music recorded — and ran into a brick wall — of sorts. Nobody thought he was ready, yet; but a kind and perceptive recording studio manager advised him to go back home to Oklahoma, where the Autrys were living by that time, get as much experience singing and playing as he could, even if he had to do it for free; and come back in a couple of years.

And that’s what he did. He picked up a new first name — Gene — worked his butt off being a telegraph operator and a traveling singer and guitar picker, went back to New York in 1929, and finally cut his first records, mostly spot-on imitations of the Singing Brakeman, Jimmie Rodgers. Gene Autry was on his way. The recording career morphed into three years on the WLS Barn Dance in Chicago, which led to a career in B-Western movies as the Original Singing Cowboy, a radio show which lasted for 16 years, his own TV show, a new career as a high-stakes but scrupulously honest businessman who made millions, and finally his establishment, in his old age, of the Autry Museum of Western History, in California.

Gene Autry certainly didn’t start out with what President Obama recently referred to as “a silver spoon in his mouth.” In this day and age, money and social position in childhood seem to be the only things our society can imagine as “advantages.” But there are “advantages” — and there are OTHER advantages. Young Orvon Autry was born with an inner drive to succeed, an ability to sing pleasingly that he developed steadily over the years, making it better and better; and the willingness to work like a dog, day and night, tirelessly, unceasingly, to succeed. And when he did, beyond his wildest dreams, he never forgot where he had come from. To friends from childhood and later, to family, to millions of fans who loved him, throughout the world, he was just “Old Gene.”

Now, when Orvon, newly re-christened Gene, was beginning his climb to the top, the Great Depression had barely started. The vast panoply of social welfare programs the federal government now operates did not begin until after Franklin Roosevelt became president, in 1932. President Obama recently said that he and his wife Michelle succeeded because they were “given” a chance. Well, Gene Autry wasn’t “given” a chance. He made his own chances, by true grit and hustle and God-given talent. That’s the American way.

But suppose, just for the sake of argument, that when young Orvon Autry was sending telegrams for the railroad, and singing for whomever would listen, that all these federal anti-poverty programs were already in place. Let’s go back a little further, and assume that they were in place when he was born, along with the various social views and beliefs that are popular now.

Orvon and his family would have been eligible for food stamps and welfare, being officially “poor.” Delbert Autry would have piddled around for a few years, half-heartedly supporting his family, until one day a drinkin’ buddy would have told him that the leg injury he received when he fell off a horse while half-soused might qualify him for “disability.” Delbert would have pursued that with an attorney, finally achieving the desire of many today: A monthly check for which he had to do nothing. He and Elnora would have learned that if they had more children, they could get a bigger welfare check. They would have reacted accordingly, with the marriage eventually producing eight children instead of four.

Young Orvon would have wanted to pursue his music, but with several types of federal assistance coming into the Autry household each month, he would have found it very tempting to kick back, sing and play for his friends, not concern himself too much about the future. If the money’s coming in without your having to turn a hand, why wear yourself out working? would become his motto.

Eventually, singing and playing occasionally around his hometown to meet girls and get drunk, Orvon would have married some local girl and settled down to an uneventful, lazy existence, much like that of his father, who lived more to enjoy himself than to do anything else. He might have worked, half-heartedly, at a series of dead-end jobs until he managed to find an excuse to apply for “disability” himself — just like his father. He probably would have gotten it, just as Delbert did.

Some day, many years later, an elderly man named Orvon Grover Autry would have died in his little town. People his own age who had known him since childhood would shake their heads and say, “Thought at one time Orvon might amount to something, with that singin’ voice he had, and them good looks. But them welfare benefits just took away all his get-up-and-go.” He would be buried in the town’s cemetery, unknown, and unmourned, by the world.

You see my point? How many famous Americans might never have emerged from obscurity, and done great things, if the tender mercies of Washington, D.C., had enveloped them at an early age? How many potentially great Americans have we lost in the years since the advent of overwhelming federal “assistance?”

Maybe, somewhere out there, there was another Gene Autry. And we never got to hear him.

10 comments for ““The Welfare State” and the Singing Cowboy”