Pete Rose, one of baseball’s all-time greatest players, has been locked in what he calls “a prison without bars” for 20 years now, because major league baseball was once so scared by a World Series sell-out scheme that it went way off the deep end about the whole topic of gambling. He should finally be released from that prison so he can be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, as nearly everyone agrees is justified by his record on the diamond.

Rose, who is not perfect by his own admission, still has paid over and over and over again, in spades, for his sin of betting on the team he was managing, and for which he had played for years, the Cincinnati Reds. Former baseball commissioner Bart Giamatti accepted an allegedly “voluntary” agreement from Rose to be banned permanently from major league baseball and from any chance to be elected to the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, NY, in 1989. The agreement was about as “voluntary” as a death row inmate’s “agreement” to be executed. Giamatti’s rigidity and Rose’s unwillingness to admit what he had done left Rose painted into a corner. Then eight days after Giamatti’s announcement, the commissioner dropped dead of a heart attack.

Flash forward to 2004. Pete Rose published a book he wrote with assistance from Rick Hill that year, admitting and detailing the fact that he did in fact bet on the Reds repeatedly while the team’s manager — but only to win, never to lose. Rose is brutally frank for the most part about his life, his personality, his career, and his gambling in the book. He admits that he denied the gambling for years because he didn’t want to ruin his chances for the Hall. Not admirable in a world that still admires truth telling; but understandable, if we’re honest with ourselves.

Rose’s predicament stems from the Black Sox scandal of 1919, and the way a panicky major league baseball establishment reacted to it. Eight members of the Chicago White Sox, American League champions that year, conspired with gamblers, for pay, to perform poorly during the World Series in order that the National League champions — ironically, the Cincinnati Reds that Rose would later star for — would be sure winners. That’s just how it panned out. Then, a couple of years later, the whole scheme surfaced, and major league baseball’s owners hired a Southern judge named Kenesaw Mountain Landis to be the new commissioner of baseball.

Landis was a hanging judge par excellence. He banned all eight players from the team now nicknamed the “Black Sox” from ever playing major league baseball again, or managing or coaching it — or being elected to the Hall of Fame. The ruling was made a part of MLB’s holy canon, and applied to all major leaguers for many times further into the future than Walter Johnson or Bob Feller could have thrown a baseball. Seventy years after the Black Sox scandal, the ruling bit Pete Rose right where he carries his wallet.

Three years after Giamatti’s sudden death, interim commissioner Jay Vincent was removed by the baseball owners and put into his place was a Milwaukee publisher named Bud Selig — who was a close friend of Giamatti’s. Hold that thought for a moment.

Selig has been every bit as emotionally constipated about the Rose case as his friend and predecessor Giamatti was. That is to say, he won’t even consider lifting the lifetime ban on Rose unless the former Red sparkplug agrees to “confess” and “apologize” publicly. And abjectly, I presume. Rose already has said it all in his book, and on several TV talk shows, but that’s not good enough for Selig. I guess he wants Pete Rose to cry and plead — probably on bended knee. Then, if he does that, Selig will condescend to consider lifting the ban. Anyone want to guess which way Selig will decide to go?

Because — and here’s why Selig should be disqualified by MLB from being allowed to decide the Rose case — Selig is emotionally committed to upholding the last major decision made by his deceased friend Bart Giamatti. He is pretending to be open to confession and contrition. But he really isn’t; he would feel that he was dishonoring Giamatti’s memory.

Pete Rose explains in his book — along with corroborating quotes from qualified psychiatrists — that he has a psychosis which not only drove him to excel in major league baseball, but also to push the envelope into the danger zone of professional gambling — specifically, gambling on baseball. It was more than Pete Rose just deciding to screw up his life, his career and his chances for the Hall. He even had to serve five months in prison on his conviction for two counts of income tax evasion. Serving time as a first-time offender for offenses like that is highly unusual. But apparently the judge wanted to “pile on” just as Selig has.

As a recovering alcoholic who also a few years ago had to struggle briefly with a mild gambling addiction, I have some idea what Pete went through with his demons. Believe me, folks, an addiction can be sheer hell. Pete Rose voiced a lot of denial, but finally came clean with anyone who wanted to read his book. He shouldn’t have to totally humiliate himself with a public mea culpa on top of that.

Gambling on baseball by major leaguers should not be tolerated; that’s for sure. But keep in mind that in 1919, most gambling was totally illegal; now we have casinos, bingo, pulltabs, state lotteries — all as legal as tiddly winks. In 1920 we outlawed alcoholic beverages. Now, they are permitted all over the country. The laws of 1919 or 1920, may not fit the realities of 2009.

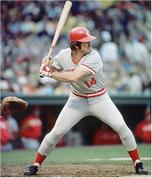

Pete Rose was more strongly identified with the city where he played than almost any other player in major league history. He didn’t have overwhelming talent like some of his more recent counterparts, but he had unlimited desire and willingness to strive for that base hit, that stolen base, that head-first slide into home for the winning run. Rose holds seven major league lifetime batting records, the most notable of which is his 4,256 career hits. Whoever thought a medium-height, stocky fireplug of a guy from Cincinnati would garner more safeties than the great Ty Cobb?

Pete isn’t getting any younger. He’s 68 years old now. Selig is 75, and wants to serve another three years, until he’s 78. Why should Rose have to out-live Selig’s term and hope for a better deal from whoever the next commissioner is?

The majority of American baseball fans in polls taken think that Pete Rose belongs in the Hall of Fame. One man — Bud Selig — shouldn’t have the power to arbitrarily keep him out. Selig should either let Pete in — or the commissioner’s employers, the major league owners, should throw Selig out.

3 comments for “Stop persecuting Pete!”