Remember how when you used to watch old B-western movies on TV as a kid (that is, if you’re about Old Corporal’s age), and sometimes there would be plot elements that didn’t quite make sense — or a feeling that something that should have been there was missing?

That was because the TV stations that showed the films cut them arbitrarily to fit the commercials into the time period allotted for the program. That meant that, if a B-western was, typically, one hour long in its complete version, about 10 minutes had to be cut out of it so the commercials could be shown — every last agonizing, irritating second of them. Cut 10 minutes out of a one-hour movie, and you’ve mutilated it. But the stations didn’t care; the commercials were paying the bills.

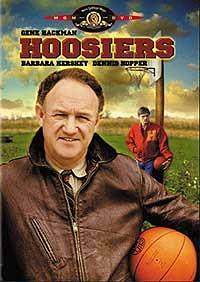

When I viewed my newly purchased two-disc DVD box set of the movie “Hoosiers” recently — that is, when I looked at the bonus material that included scenes filmed but then cut from the final version of the film — I realized that what is a great sports movie, probably the best of all time, could have been a true American epic. It could have been, but it isn’t. Why? Because the money men, those financing the movie, were determined to keep its length down below two hours.

Director David Anspaugh and screen writer Angelo Pizzo discuss the scenes, pointing out that most of them should in their opinion have been left in. But their hands were tied. As usual, the Golden Rule applied: Those that had the gold, ruled. They wanted a moderate-length movie about basketball — not an epic film about the extraordinary love the people of a mid-sized Midwestern state held for a pastime that brightened their long, dark winters in the 1950s; about how several people managed to achieve a second chance at success after personal failures; or about a romance that matured in spite of itself, leaving a question mark at the end that suggested “sequel”.

What do the deleted scenes show? Well, a couple simply add detail to Norman Dale’s arrival at the little Indiana town of Hickory to be the new high school basketball coach. A not-terribly-friendly man who pumps gas for Dale at a neighboring small town turns out later to be the coach of one of Hickory’s rival schools. The principal at Hickory — Cletus, played by Sheb Wooley — walks the new coach and teacher through the halls, talking about the job and Hoosiers’ love affair with basketball. As they go outside, Dale pauses suddenly to stare with admiration at a young female teacher (Myra Fleener) lollygagging with a young male teacher in the parking lot. Then his face tightens with an expression that says clearly, “Well, you’d never have a chance with HER, you old goat,” and continues to follow his new boss.

Cletus does indeed have a home and a family — not really made clear in the finished film except for the scene where the two look over the fields outside the barn and talk of Jimmy Chitwood. Norman Dale eats dinner with Cletus, his wife, and their brash, talkative teen-age daughter, who wants to know if Dale is married (he’s divorced) and if he goes on dates. She also asks, “Have you ever seen television?” and tells him that the nearest movie theater is 20 miles away. It broadens our knowledge of Norman Dale as the finished movie does not. He didn’t just fly in from Mars last week and start coaching basketball. It also helps locate “Hoosiers” in a place in time — the early 1950s, when TV was just starting to spread across the country. It hadn’t reached Hickory yet.

The next deleted scene is a classic, one of the most moving I’ve ever scene. The whole community shows up to harvest corn in a field outside the little town. The scene is shown without sound other than a musical track. Silhouetted figures are shown going into the field, beginning their day’s work; the fact that they are in shadow silhouette universalizes them — they could be in Iowa, or New Hampshire, or north Germany. Norman Dale pitches in with a will, helping out with enthusiasm if not outstanding skill. Various team members are seen taking part — they DO do things besides play basketball. At noon the farm laborers are shown eating at picnic tables; in late afternoon, their work almost done, relaxing against big corn shocks.

The scene is sheer poetry — it could be a painting of Flemish farmers in the fields by Pieter Brueghel, a Peter Paul Rubens painting of a harvest festival, or Jean-Francois Millet’s 19th Century “The Gleaners.”

In a scene that IS in the movie, a player named Buddy is kicked off the team by Dale at the first practice when he “wises off” at the new coach. He later transfers to a neighboring, rival school. But in a deleted scene, he approaches Dale where the latter is relaxing with a book in Cletus’s barn (there is a window showing a view of Cletus’s fields just to the viewer’s left of Dale in the shot, and it is a beautifully composed scene). Buddy humbles himself, telling Norman Dale that he just couldn’t play for that team that has been “the opposition” all his life, and asking if he can have another chance. Dale says, “If it’s OK with Cletus, it’s all right with me.” This resolves the often-puzzled question from “Hoosiers” viewers, “How come Buddy’s back on the team in later scenes?”

Myra Fleener’s scenes were severely cut by the money men, and actesss Barbara Hershey who played Dale’s love interest in the film was reportedly very unhappy with her truncated role. The deleted scenes show her in a much more nuanced view — a girl from a small Indiana town who went to Chicago with big dreams, had some kind of a terrible experience there (never specified in either the finished movie or the deleted scenes), and ran back to her home town to lick her wounds — but never reconciled herself to that return and was left feeling frustrated and bitter.

The most grievous loss from the finished film is the scenes developing the character of Opal Fleener (Fern Persons), Myra’s mother, with whom she lives. Opal is feisty, opinionated, and not happy that her daughter won’t take her life in her own hands and do what her heart tells her to. Opal and Norman develop a close, almost chummy relationship.

Finally, there is the scene showing the motorcade leaving Hickory en route to the state finals, and Myra telling Norman as he bids her good-bye that she won’t be teaching next year — she’s enrolled in college courses in Chicago. It was his example that inspired her to grab for the opportunity to get out of Hickory, she says. Norman’s stare of surprise, shock and disappointment, all combined, is matched by Myra’s expression of understanding, and regret, that she has wounded him. But they bestow a chaste little “Good-bye” kiss on each other, and he promises to come see her when she gets settled.

You see? With those scenes added, the film makes much better sense. Hickory is a tiny town that’s behind the times — but its people have important strengths, such as banding together to help each other. Buddy leaves the Huskers in a moment of anger, but has the character to come back, admit he was wrong, and ask to be reinstated.

Norman Dale has a past that includes more than an aborted college coaching career and several years in the Navy. Myra Fleenor’s bitterness is traceable to disappointment with the course of her life. Her mother’s desire to have Myra do whatever will make her happy — even leave, if it comes to that — helps to explain the friction between the two.

Include the omitted scenes, and you have a longer film — but not tremendously so. The longest missing scene is probably five minutes in duration. What’s more important is, you would have a much more well-rounded film, in which people’s lives and motivations are explored, and, happy ending notwithstanding, we are left wondering what will happen between Norman and Myra.

The money men were satisfied with a movie about basketball — a run-and-gun. If they hadn’t been so worried about the bottom line, they could have made something that would rank with the truly great films. Perhaps some day whichever entity owns the rights to “Hoosiers” will put those missing scenes back in.

Let’s hope they show us “the rest of the story.”

1 comment for ““Hoosiers” — the rest of the story”