(I wrote this short story, about a young boy and girl in modern times whose fascination with the “Singing Cowboy” Gene Autry leads them down roads they never imagined, several years ago. Hope you enjoy it.)

——

“Who’s Gene Autry?” asked Tommy Chapman doubtfully as his father, Art, inserted a video into the family TV set one evening after supper.

“Why, son, Gene Autry was my hero when I was your age,” answered Art, and his blue eyes grew cloudy at the memory. He stopped what he was doing to stare off into space, seeing things visible only to him.

“Me and Eddie Tatum used to beg a quarter or fifty cents from our moms every Saturday so we could go down to the Bijou Theater and watch Gene and his horse Champ and Pat Buttram, or Smiley Burnette, his two pals. Wasn’t nothing ole Gene couldn’t do when it came to riding that big horse, shooting the six-gun out of the bad guy’s hand, knocking him for a loop with a good right cross – and saving the pretty girl’s ranch for her,” Art said, still frozen in place, his memories racing.

Tommy, 10 years old, restless, wiry and red-headed, shifted on the floor impatiently as he tried to play his hand-held video game and listen to Art at the same time. “But Dad, who was Gene Autry? WHAT was he?”

“Just the best damn cowboy that ever lived, little hombre,” said his dad, smiling as he came out of his reverie. He punched the play button, settled down into his recliner, and said, “Tommy, I’ve neglected your education sadly up to now. Don’t know why I never thought to get some videos of Gene’s movies, so you could see just what he was like. Well, boy, here we go!”

The movie spun into action, and Tommy soon let his video game rest ignored and forgotten on the floor. A new world opened up for him on the screen, a world populated by western-hatted outlaws and sheriffs, galloping horses, barking six-guns, and pretty young women in long, denim gowns.

And especially by a medium-sized cowboy in a big white hat, who rode a tall sorrel horse and rode him hard; spoke with a casual western twang; and sang songs in a rich, syrupy baritone (Art had forgotten to tell him about the singing part). Something in Gene Autry’s slightly awkward but pleasant demeanor, his sincerity, the impression that he was just one of the boys, but somehow a natural leader, appealed strongly to Tommy Chapman, who had never before had a real idol. Something about the friendly cowboy, that bad guys messed with only at their peril, spoke to a place in Tommy’s soul which hadn’t been reached before.

Tommy became a devoted fan of Gene Autry – especially after his dad mentioned that Autry, now a very old man, was still living, out in California, and the owner of a major league baseball team.

The boy wanted to see more Autry videos, to soak up the essence of his newfound idol. His father, seeing his own boyhood hero worship echoed in his son, was happy to oblige. Next came Autry CDs, so Tommy could hear Gene sing of his home on the range and tumbling tumbleweeds and an empty cot in the bunkhouse tonight – and Rudolph, whose little light shone at just the right moment.

The Chapmans lived on a small farm – Art worked in a factory, too, though – and Tommy next begged for a pony that would look as much like Champ as possible. Art and Molly, Tommy’s mother, had to mull that one over for a while. A pony was quite an investment for their income.

Finally, they decided that the purchase would be made – but Tommy had to agree to start paying them back with the money he earned carrying newspapers in the neighborhood.

Of course, no deadline was set for completing the payback.

When Little Champ took up residence in the stall Art and Tommy built for him in the garage, and Tommy had learned to ride him – albeit after some painful spills – Tommy put aside the bike he had used for his paper route, and began riding the pony on his rounds. His grandmother, who had watched an even younger Gene Autry when SHE was young, was delighted by his idol worship of the Singing Cowboy, so she got together a cowboy outfit as much like a typical one of Autry’s as she could find, complete with cap pistol.

As Art watched Tommy saddle Little Champ one day, he said, “Say, son, if you want me to get you one of those bridles with the two six-shooters on it, like Gene used to have on Champ, I’ll see what I can do.”

Tommy stopped settling the pony’s bridle into place and slowly turned around to stare at his dad. There was a shocked look on the boy’s face.

“Oh, no, Dad! Thanks for offering, but only Gene Autry’s Champion is allowed to wear that special bridle!”

Tommy had watched the Autry movies his dad provided him, fascinated by many things. But he became positively fixated on the unique, double six-shooter bridle. He noticed that no other horse in any of Gene’s pictures had such a bridle. Hence the conclusion he reached: The double pistol was a distinctive, one-of-a-kind decoration that belonged to Champ, Gene’s big, beautiful sorrel, and to Champ alone.

The child was so obviously sincere and adamant that Art shrugged off the matter and soon forgot it.

Tommy’s riding of Little Champ to school, while wearing his Autry outfit, produced the first sour notes in his hero worship of the singing cowboy.

“You dressed up for a masquerade?” asked a mean 12-year-old, Todd Bailey, the first time he saw Tommy on Little Champ. “What’s that cowboy outfit for?”

“I’m dressed like Gene Autry, the greatest cowboy of all,” said Tommy proudly, dismounting and tying Little Champ’s bridle to the school fence.

“Gene who? Never heard of him!” sneered Todd. “Hey, Joey, dig my cowboy hat!” he yelled to another sixth-grader, grabbing Tommy’s hat and putting it on his own head. “Ha! Ha! Ride ‘em cowboy!”

Todd skimmed the hat to Joey through the air, and they tossed it back and forth like a frisbee as the younger Tommy raced to and fro, trying to grab it. Joey finally sailed it into a mud puddle, provoking loud hilarity on the part of himself and Todd, and sputtering rage from Tommy.

“You ruined my cowboy hat!” he yelled, running at Todd with fists flying. The bigger boy easily sidestepped Tommy, then walloped him hard in the head. Joey jumped in to get in his licks also, and by the time Miss Ellison the teacher had rushed over to short-circuit the fight Tommy was bloody-nosed, black-eyed and weeping.

Tommy continued to ride Little Champ to school – he was stubborn as a mule, that little kid – and was given a hard time by other boys until the novelty of it wore off. All the kids thought him a little weird for idolizing a man who hadn’t made a movie for almost 50 years and was now 90 years old, and no one else shared his love of Gene Autry.

No one, that is, except Conchita Ramirez.

Conchita was a chubby, pretty little Mexican girl in Tommy’s class. She was also the only other child in the school who knew anything about the Singing Cowboy.

Conchita’s Grandmother Esmerelda told her often of how she and her friends down in Mexico had loved the Autry movies when she was a child. On her vanity in her bedroom, Grandmother Esmerelda kept a faded old photo of Gene Autry as a young man. She often held her granddaughter spellbound with stories of how many of Autry’s movies were set in Mexico or in parts of the Southwest where many Mexicans lived; how numerous songs he recorded had Hispanic themes, and how he even sang some in Spanish. Gene had an excellent accent when he sang in their native language, Conchita’s grandmother told her.

Why, there was even a deep mystery surrounding one of Gene’s Mexican songs, “Noches Eternas” , the old lady told her starry-eyed granddaughter. The title meant “Eternal Nights.”

“There is an old legend told in the villages in northern Mexico, about how Gene recorded ‘Noches Eternas’ early in his career — but what they called the ‘master disc,’ the thing they made the recording on, disappeared from the recording studio before they could ever get copies pressed to sell in the music shops. Your great-grandfather — my father, Pedro Herrera — worked as a young errand boy in that studio; he had crossed the Rio Grande into Texas a few years before. I still remember him telling me how he heard Gene record the song. He said it was the most beautiful Mexican music he ever listened to. But Gene’s version of the song was never heard by anyone but those in the studio, because the master recording was gone.”

“What about the big mystery, Grandmother?” asked Conchita, leaning forward now, enthralled by the old lady’s storytelling.

“Well, for one thing nobody ever found out what happened to that master disc. But here’s the real mysterious thing, my child: For years, when I was growing up in Mexico, we would hear that the peasants in a neighboring village had somehow found a copy of the record, and played it, and of how beautiful the music was, that it made the women cry, and the men moan. And in the next village, they would hear the same rumor, about OUR village. But I never heard of anyone who could actually say that he had heard the song. It was like what Gringos call a ‘Will ‘O’ the Wisp’ — something that’s always just beyond your reach, that you can’t quite focus on or make out.”

Old Esmerelda’s stories started a longing in Conchita to learn more about this Norteamericano cowboy who was a young, handsome man so many years ago, who could sing her country’s songs so beautifully, who fought always on the side of the right and treated women and children, like herself, with such gallantry and kindness.

She had noticed her red-haired Gringo classmate who wore the odd, old-fashioned cowboy clothes to school. But she never made a connection between him and her idol from the long-ago movies until she heard some other children teasing him one day: “Gene Autry! Gene Autry! Who the heck is Gene Autry?!”

Tommy Chapman had grown accustomed to the ribbing about his obsession by now, and he walked away from the other kids, heading over to the fence where Little Champ was cropping grass. He held the pony’s head, whispering to him, “Never mind, fella; they’re just ignorant. We’ll show ’em, one of these days.”

Conchita approached her male classmate timidly. They were at the age when boys and girls definitely are dividing into “us” and “them” camps, and Conchita wasn’t used to talking to Norteamericano boys one on one.

“Uh, hi,” she said. Tommy started, unaware anyone was near. “Oh, hi. You’re in my class, aren’t you?”

“Yeah.” The girl was gazing at the pretty pony with his sorrel color, his white face blaze and socks, so like the real Champion.

“I heard those other kids saying, ‘Gene Autry’ to you, like they were making fun. What do you know about Gene Autry?” she asked shyly.

Tommy turned and stared at her. “Well, what do YOU know about him, and how did you find out?” he replied.

Conchita related how her great-grandfather had worked with Autry in a recording studio, many years before. Tommy told of his dad’s introduction of him to the Singing Cowboy, and of how he since acquired a large collection of his movies and watched them incessantly, of how he thought Gene was the greatest cowboy who ever lived.

The girl’s dark eyes widened. “You have films of Gene Autry? I’ve never seen a picture of him except an old one my grandmother has in her bedroom.”

“Videos,” Tommy corrected her. “You pop them into your TV set and they work just like a TV program.” He knew he had sounded like a know-it-all when he said that, because Conchita’s eyes flashed with annoyance. “I know what a video is, and what you do with it,” she snapped.

“OK, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to rile you,” the boy answered. He pretended to straighten Little Champ’s bridle for a moment as he mustered up his courage; then said, “Say, if you haven’t seen one of Gene’s movies, would you like to come to my house and watch one with me?”

Conchita faltered slightly, took a step backward. “Come to your house? Why, I just met you. I — I’d have to ask my grandmother first … I, I don’t know …” With that she turned and ran away. Tommy watched her go, disappointed and annoyed all at once. “Girls!” he said with disgust. “Come on, Champ, let’s get out of here.” He swung into the saddle and rode off toward home, to play hooky the rest of the day.

Conchita told her grandmother that night about talking to the Gringo boy, and discovering their mutual fascination with the Singing Cowboy.

“He asked me to come to his house, and watch a Gene Autry video!” the girl said, her eyes gleaming with excitement. “Do you think I could, Grandma? He’s … uh … he seems like a nice boy, but I don’t know him very well, and …”

Old Esmerelda smiled indulgently. “If it’s all right with his parents, and at least one of them is there, then it’s OK with me if you go,” she said.

Conchita saw Tommy the next day on the playground, and said, “Well, I asked my grandmother (I live with her), and she said if it’s OK with your parents, and one of them is there, then I can come and watch a Gene movie with you.”

Tommy realized he hadn’t asked his mom or dad about the invitation. But when he broached the subject hesitantly that night at supper, they had no objections at all.

“A little Mexican girl who’s interested in Gene Autry, too?” said Molly, chuckling at the idea. “That’s neat! Bring her on home; I’ll be here all afternoon.”

“Maybe you can give her a ride on Little Champ,” said Art. Tommy wasn’t so sure about that, though. Little Champ had been ridden by no one but him, and he had unpleasant mental pictures of Conchita falling or being thrown off and never being allowed to come over again.

A few days later, Conchita’s grandmother dropped her off at the Chapmans’ farm after school. The two children had decided that for her to ride the bus home with him would have sparked more teasing from the other kids than either wanted to endure.

Tommy’s mom smiled with amusement when she saw he was taking special pains in wetting down his rusty hair so it would lay just so. Conchita wore her nicest dress after Esmerelda ironed it with special care for her.

Plied with cookies and milk by Molly, the two fourth graders settled down in front of the TV. Tommy produced a video from the collection his dad had bought for him and said, “For your first Gene Autry movie, Conchita, I’m gonna show you ‘South of the Border,’ and it’s set in Mexico.”

The film, one of Autry’s most famous, stole the young Mexican girl’s heart — especially his singing, and the romance between him and Lupita Tovar, the beautiful Mexican senorita. Conchita cried softly at the end when Gene’s Mexican sweetheart joined a convent to atone for her late brother’s evil ways, leaving the Singing Cowboy alone to make his way sadly back across the border. Tommy winced at the crying, but concluded that was just a girl thing he couldn’t do anything about. He loved the action scenes and Gene’s hell-for-leather riding of Champ. He also laughed at Frog Milhouse’s comic antics, but Conchita thought Gene’s rotund sidekick was just silly.

Molly invited Conchita to come back again in a week and watch another Autry movie. So on that day, she was surprised to see Tommy and his little Mexican friend get off the bus together. Molly met the two at the front door, giving her son a questioning, bemused look. He knew what she meant, glanced at Conchita, and said, “Aw, let ’em snicker.” Conchita gave her hostess a conspiratorial little smile.

The weekly visits settled into a routine, in which the two children would watch a movie, then go outside to fuss over Little Champ. While Conchita never became as comfortable in his saddle as Tommy, she eventually learned to ride him around the yard without fear of falling off. When Tommy yelled, “Attagirl, Conchita! Ride ‘im, cowgirl!” she would laugh, and Little Champ would pick up his step a little, as if proud to be hauling a guest.

One day while they were watching their weekly Autry movie — Tommy sprawled on the floor, Conchita curled up in a chair just above him — Tommy suddenly said, “Tell me just why you like Gene so much.”

“Well,” she said, munching a cookie and gazing at the screen, “For one thing, he’s very handsome.” She added archly, “Us girls like that, you know.” Then she went on, “He’s such a good guy — but he’s what Mexicans call a ‘muy mucho hombre’, too — very much a man. He won’t let anyone push him around. And his horse is beautiful, and smart. And he just looks so right when he’s riding Champ. And of course he sings Mexican songs like an angel. Hey, you still there?” she asked, nudging Tommy with her foot, as he hadn’t answered.

“Yeah, I’m listening,” he said finally. “I was thinking about what I asked you. I like Gene because — well, mainly the things you said. Except the handsome part. Although I like the way his hair hangs over his forehead after he’s had a fight with a bad guy. Makes him look real regular. And his cowboy clothes are neat. And I like Frog and how he and Gene are real tight, even though Gene teases him a lot. You can tell they really were buddies — it wasn’t just in the movies. Say, how come you don’t like Frog?”

Conchita squirmed, reluctant to speak badly of the chubby sidekick when Tommy obviously liked him. But finally she said, “Well, he’s got his good points, I guess. He really does sing good, if you listen to him. And sometimes he helps Gene out in fights and stuff. But he just acts so darn silly sometimes. He really overdoes it.”

Tommy said there was something else about Gene Autry that he had forgotten to mention — something his dad had told him about.

“When Gene would go around the country and make these what they called personal-appearance tours, he would always visit any little kids who were in the hospital in the town where he was. He always did that. He’d talk to ’em, sing to ’em, try to make ’em feel better. Dad said my grandpa was one of those kids he visited. Said Papaw talked about it for the rest of his life.”

The movie, “Rootin’ Tootin’ Rhythm,” was nearly over. Gene was singing “Mexicali Rose” to the Mexican girl who was his love interest — and who he would have to leave before the final fadeout. Tommy suddenly got up and sat beside Conchita. As she watched and listened to Gene sing, she suddenly was aware of another sound — like the Singing Cowboy was doing a duet with an invisible partner.

Then she realized — Tommy was singing the song, too. Singing it to her. She glanced sidelong at him and saw that he was staring straight ahead, embarrassed at his own temerity, his face as red as his hair. His voice wasn’t that good — but he kept singing. Then he turned his head toward her, and smiled.

Conchita was overwhelmed. She blushed too — then quickly looked away, back to the screen, where Gene reared Champion proudly at the gate of the ranchero, bidding goodbye to the girl who was crying and waving her handkerchief at him from the front door.

Conchita felt a hard, bony little hand slip into her chubby, soft one. No words passed between the two, but she squeezed Tommy’s fingers tight.

Before Conchita ran to her grandmother’s car that day, she put a quick, shy kiss on Tommy’s cheek, whispering, “See you soon.” He blushed again while he watched her jump into the car, then wave good-bye as the old lady drove away.

“Mom,” Tommy asked hesitantly after supper, straddling a kitchen chair as she washed the dishes. “How old do you have to be to fall in love?”

Molly stopped what she was doing to look searchingly at her red-headed, intense little boy. “Now son, I know you and Conchita really like each other a lot. But remember you’re only 10 years old. There’ll be plenty of time for ‘love’ when you’re older and — well, more mature. Be content just to be good friends for now. OK?”

Tommy looked doubtful and a little disappointed. But he said, “OK, Mom,” and began drying the dishes.

At her grandmother’s house, Conchita was brushing her hair at about the same time. It was her nightly ritual.

“Grandma, do you know Tommy held my hand today while we were watching Gene’s movie?” she asked.

Esmerelda looked up from her crossword puzzle, smiling but with a little concern. “Well, honey, that’s probably just his way of showing he likes you,” she said. “You two are just little muchachos. Just two friends with a common interest. Enjoy it and just be the kids you are.”

“I kissed him good-bye before I left, Grandma,” said Conchita, looking steadily at the old lady. “Yeah, we’re just little kids now. But someday we’ll be all grown up.” She turned away and said quietly, “And then I’m going to marry Tommy.”

Hours later back at the Chapman house, his homework painfully done (Tommy was only an average student), the young buckaroo sat on his bed, thinking about how that one video his dad had shown him a couple of months ago had changed his life. Conchita was special to him — but he would not have gotten to know her without Gene Autry. The thought that as Autry was now a very old man, and Tommy would never get to meet him, had been preying on his mind lately, and the boy felt a pall of sadness. Why had he been born too late to really get to know the Singing Cowboy?

The light in the room seemed to become brighter, but Tommy was too engrossed in his thoughts to notice. Then —

“Whuhuhuh!” It was a horse’s soft nicker, close at hand. Tommy jumped, startled, then cautiously looked around.

“Hello, Tommy! Hope you don’t mind Champ and me paying a little visit!”

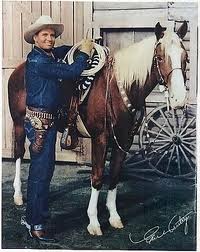

The boy held his breath, not believing his eyes. Gene Autry and his beautiful sorrel stood before him, right in his own bedroom, with Gene smiling that famous Autry grin and Champ regarding Tommy with curious, intelligent horse eyes. Gene looked young and energetic as he did in his movies; he wore the famous white hat, the navy-blue shirt with the arrow pockets featured in so many of his late-30s movies, and his striped range pants and ornate high-top cowboy boots. Even in his shock, Tommy’s eyes were drawn to Champ’s famous double six-shooter bridle with its pearl handles.

“G-Gene! How did you get in here? I mean, are you for real?” the boy stammered, standing up shakily.

“Real as Christmas, Tommy! Here, shake my hand,” Autry said genially, extending it and gripping Tommy’s little paw. Tommy noticed that Gene’s hands were unusually large for those of a middle-sized man — ideal for twirling a lariat, gripping a six-gun, or punching a bad guy in the jaw. The Singing Cowboy’s firm grip left no doubt: He was there in the flesh, all right. Tommy reached out a trembling hand, stroked Champ’s head. The horse nickered again, gently, as if to say, “It’s OK, son; kids are some of my favorite people.”

Tommy had begun to regain a little aplomb after his initial shock. “What’s up, Gene? What brings you here to my house?”

Autry grinned mysteriously, reached up to push his hat back on his head in a gesture familiar to Tommy from his movies.

“Well, Tommy, I heard that you sort of like mine and Champ’s pictures, so I thought if you didn’t mind I’d take you on a little tour through them,” he said. Tommy was stunned by the offer. Then he decided that if Gene Autry could appear before him one night in his own bedroom, then it was logical that he had somehow learned of Tommy’s hero worship.

“Yeah, gee! You mean we’ll see all your movies?”

“No — that would take too long. You might say that we’ll ride and walk through a sample of my life,” Gene answered. “Want to take a good look at Champ, up close, before we go?”

Tommy moved closer to the big animal, stroked the sloping forehead and nose, the noble neck. Champ again regarded him, as if he were looking the little boy over curiously too.

The boy took tentative hold of the precious six-shooter bridle. “This is beautiful, Gene — and Champ’s the only horse allowed to wear it. Right?”

Autry smiled, didn’t answer, then said, “Well, come on, little pardner, and let’s ride. Champ gets a little edgy if he stays in close quarters like this for too long.” He swung Tommy up into the saddle, then mounted behind him, grasping the reins. “Chck! Chck! Let’s go, boy!”

The horse sprang forward, began to canter. The room disappeared suddenly; then they were out in the clear night sky, galloping past the stars. Tommy held his breath, then let it out in a “Whoosh!” He couldn’t believe what was happening.

“Hang on, son, we’re heading into the light!” yelled Gene. Daytime suddenly flashed up around them, and the night sky was gone.

Champ pulled up and came to a stop. Tommy looked around. They seemed to be on a seedy little ranch, beside a ramshackle little house.

“Is this part of your first movie, Gene?” the boy asked.

“Naw, Tommy, this is where I was born. My dad had a little spread here — raised horses. But he was gone a lot. Wasn’t what you would call a good father — not like your dad. Why, there’s my mom!” said Gene, as a young but care-worn looking woman came out the front door, wiping her hands on her apron and looking around. “She won’t be able to see or hear us, though.”

“Orvon! You’ll be late for school!” she called.

“I’m comin’, Mom. Just finished up splitting this wood,” a boy’s voice answered from behind the house.

“Who’s Orvon?” asked Tommy. “That’s me,” Gene said, grinning. “I changed my first name later on.”

A boy about Tommy’s age, blond haired, blue eyed and slim, came running around the corner of the house, his arms full of kindling. He carefully deposited the wood on the porch, ran inside and returned with some school books.

“Mom, when’s Pop coming home?” young Orvon said plaintively, craning his neck to look into his mother’s eyes.

“When he’s ready, son. Now get on to school,” she said, forcing a smile for him.

Orvon sighed in resignation, ran off down the road with his books.

“When he gets tired of that slut, I reckon,” Mrs. Autry muttered to herself, wearily re-entering the house.

Tommy asked Gene where his father had gone. “Hunting,” Gene said. “Now, son, we’ve got to move on.”

The scene changed, melting like a dissolve in one of Gene’s old movies. They stood on the outskirts of a crowd of people in the main square of a town. A medicine-show wagon like the ones Tommy had seen in several of Gene’s movies was set up in the midst of the crowd. A man in a colorful suit and top hat stood on the platform, bellowing, “Next in our splendiferous entertainments, ladies and gentlemen, is the expert saxophone tooting of young Orvon Autry. Let ‘er rip, Orvon!”

Tommy saw a teenage boy, who he recognized as an older version of the youngster at Gene’s birthplace, step forward and begin playing “Oh, Susanna!” on a brass saxophone. He didn’t sound that good to Tommy’s ears, but when he finished the crowd gave him a round of applause and he bowed, sweeping off his cowboy hat as he did so.

The man in the top hat came forward again, intoning, “Now, friends, let me tell you about Dr. Parker’s Painless Panacea …”

“I worked on this medicine show the summer I was 15 years old,” Gene said. “Then I went back home, because my folks needed me on the farm.”

“I never knew you played the saxophone,” said Tommy. “Just the guitar.”

“I started out playing the sax, but then I realized I couldn’t sing and do that at the same time,” chuckled Gene.

Tommy sensed that it was time to go. The landscape whirled around them like the inside of a kaleidoscope. When things slowed to a stop again, they were standing at the entrance to a cave. A group of riders in strange, other-worldly outfits with helmets like kitchen pots that hid their faces galloped out, roaring right past Gene and Tommy without a glance.

“This is where my film career all started, Tommy; ‘The Phantom Empire,’ ” Gene said. “Those were the Thunder Riders from the lost city of Murania.” Tommy hadn’t watched the serial yet, but he had read a summary of the plot.

“Can we see Queen Tika?” he asked. “Sure,” Gene said. The scene changed to the queen’s throne room, where she stood surrounded by her advisers.

“You said they can’t see or hear us? I wish she could,” Tommy said wistfully.

“Oh, we can arrange that,” Autry said. “Go ahead, say something to her.”

Tommy cleared his throat, then called, “Hi, Mrs. Queen!”

The queen looked up. She was tall, regal and beautiful. “Why hello, Tommy! Welcome to my kingdom!”

“Gosh! She knows my name!” he marveled.

Autry told the queen he was taking Tommy on a little tour of his career. “Well, Gene was a mighty young cowboy when he first came down here,” she laughed.

“Say good-bye to the queen, Tommy; we’ll take a zoom through the streets of Murania on our way to our next stop,” Autry said, as Champ charged up the steps from the throne room at a gallop. “Bye, Mrs. Queen!” called Tommy as she waved to him.

Champ raced at top speed through the streets, but the boy still got a good look at the fantastic-looking buildings, bridges, vehicles and people of Murania. “The Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials were influenced by this one,” Gene called into Tommy’s ear over the street sounds and clippety-clop of his horse’s hooves.

“Who?” Tommy yelled back, mystified. “Never mind; I’ll tell you some other time,” answered Autry, smiling to himself.

The kaleidoscope spun again, and suddenly they were pounding down a trail through desert land near some beautiful mountains. Tommy looked up ahead and saw another man on a horse, trying desperately to keep ahead of them. Peering over his shoulder, the boy spotted other riders trailing behind.

“Where are we now, Gene?”

“This is the horse race in ‘Comin’ Round the Mountain,’ ” Autry shouted. “That’s the head bad guy, Leroy Mason, up ahead of us.”

Champion gained steadily on the other horse, stretching himself out at full gallop to catch the pinto which he hated; that was part of the story. As they pulled up alongside, Mason’s character looked at Autry, whipped his reins at him to try to break his control of the horse, and shouted, “Blast you, Autry!” Then he spotted the boy and added, almost casually, “Oh, hi, Tommy! Better hang on!”

Gene’s big sorrel nosed ahead of the pinto as they neared the finish line in the town, winning by a clear length. As the crowd cheered, Champ kept right on going — because it was time to turn another page in Autry’s saga.

They sped through a whir of landscape and characters again, finally coming to a halt in front of a big, austere looking building with tall gates.

“Where is this, Gene?” asked Tommy as they dismounted.

“It’s a Spanish mission in Mexico, son,” the cowboy said, removing his hat as they entered the building. “This is where I found out that the girl I loved had joined a convent, because her bad brother had disgraced the family.”

They entered the chapel, Gene holding a finger to his lips for quiet. Tommy looked down the center aisle at the beautiful, mournful sight of Christ on the Cross — then was surprised to see someone dressed in a long, white habit with a veil enter from his left. It was a lovely senorita, who knelt quietly at the altar and stared up at the crucifix, her lips moving soundlessly.

“Who is she, Gene?” asked Tommy. “That’s Dolores, the girl I love,” Gene whispered back. His face looked dark and unhappy. “I can’t marry her now, Tommy, because she’s become a nun. Come on, son, we have to leave. Besides, this scene always makes me so sad.”

Silently, they tiptoed from the chapel, out of the front gates, and re-mounted Champ.

“You know, Tommy, in a way I was always glad they ended ‘South of the Border’ that way. It shows people that life doesn’t always tie up all our loose ends before we ride off into the sunset.” Tommy turned to stare at Gene, not fully comprehending what he meant.

The big sorrel galloped off down the trail, and suddenly the world began to spin again, until Tommy was dizzy. He heard what sounded like a huge crowd — like maybe at a baseball game where Gene’s team was playing, he thought. But the people didn’t sound like any baseball fans he had heard.

Then the setting began to come into focus; he could see that he and Gene were standing on a balcony of some kind of a large building. They were in a big city — but it didn’t look like the few cities Tommy had been in. The buildings weren’t as tall, and they looked much older.

Down below in the street was a huge mob of shouting, seemingly happy people, all looking toward them. He could hear some of the things they were saying. It was English — but with a strange accent he didn’t recognize.

“Good on yer, Gene, ould boyo!” “I’ll drink a pint in yer honor tonight, I will!” “Sure, I’ve missed divil a one of yer pictures, Mr. Autry!”

“Where in the world are we, Gene?” asked Tommy, bewildered.

“We’re in Dublin, Ireland, Tommy. I made a personal appearance tour here, just before World War II started. Drew the biggest crowds they’ve ever seen in Ireland, if I do say so myself. We’re on the hotel balcony where I stayed here; this is my last night in the country, and these Irish people are serenading me. Here them singing now? That song’s called ‘Come Back to Erin.’ Had the most fun here I ever had in my life. Those Irish girls sure were something!”

One man, spotting Tommy, shouted, “I don’t know who ye are, lad, but if yer with Gene Autry you’re foin in my book!”

But then the scene began to change again, the crowd to grow blurry, their shouts to fade gradually, gradually away …

Tommy looked around again. They were in front of a ranchhouse on a prosperous-looking spread.

“This is one of the sets for a movie of mine from 1940. Well, several movies,” Gene said, with a roll of his eyes.

A pretty young girl, 13 or 14 years old, came running from the house, closely followed by a willowy, beautiful young blonde woman.

“Why, that’s little Mary Lee, who sang so good in your movies,” cried Tommy. “And that lady is June Storey. She was your sweetheart a bunch of times, wasn’t she, Gene?”

“Yeah,” the Singing Cowboy answered.

Both rushed to Autry, throwing their arms around him for hearty hugs. Then they spied the boy.

“Why, it’s Tommy! You brought Tommy with you! Look, June, isn’t he just cuter ‘n a speckled pup?” Mary gushed. The teen grabbed the boy in a big embrace, kissed him wetly on the cheek. “Hey! Cut it out!” Tommy yelled, his prepubescent male pride outraged. He jerked away angrily.

“Tommy’s not quite ready for that much enthusiasm from a girl,” said June Storey, grinning. She encircled him carefully with one arm for a more chaste greeting. “But there’s a little Mexican girl I bet he’d love to hug — right, Mary?”

Both females laughed knowingly. “Ah, jeezelpete, Gene, let’s get out of here!” sputtered Tommy, embarrassed and mad all at the same time.

Autry chuckled understandingly, a reassuring hand on Tommy’s shoulder. The kaleidoscope whirled again, and they were watching a freight train rushing past, crossing the prairie. They could see the movie version of Gene Autry on Champ, galloping alongside. He hesitated, then grabbed the ladder on a freight car and swung from the horse’s back to the speeding train. He climbed up the side of the car, reached the top, then ran along it toward the locomotive, in pursuit of the fleeing bad guys.

“Wow! Neato! You did that transfer yourself — no stuntman!” Tommy cried, his momentary embarrassment forgotten already.

“Yeah — I did a few of those myself, along,” Gene answered matter-of-factly. “I liked that. But most of the directors wouldn’t let me — afraid I’d get hurt, and then shooting would be held up. That would cost the studio money. Republic was always watching those nickels and dimes.”

As he spoke, the train and the prairie slowly melted away like snow in July. Suddenly they were standing in a hallway in some type of public building. Closed doors punctuated every few feet of the walls. There was a number attached to each door.

Gene looked at Tommy with an odd expression — partly pained, partly determined to do what was right.

“Where’s this, Gene? Are we in another movie?”

“Just watch for a minute, Tommy.”

Suddenly a young man and woman appeared in the hallway. Tommy recognized the man as Gene; the woman had black hair, but the boy couldn’t quite make out her face. They stopped at a door, Gene opened it, and the young women entered. Gene glanced around as if to make sure he wasn’t being watched. Then he followed her in, and the door closed.

“Gene, was — was that your wife?”

Tommy looked into his idol’s face and was surprised to see tears standing in his eyes. “No, Tommy, she wasn’t,” Autry answered — and suddenly the boy noticed that Gene looked a little older, a little heavier, than he had a moment ago.

The cowboy said he would explain the scene later. “I had to show you that, Tommy. It wouldn’t be right not to. And now we’ve got to move on again.”

The hallway disappeared. Now they were in a tavern — or a saloon, as Tommy thought of it, having seen them in many Autry movies. They were the places where Gene would enter, saunter up to the bar, and when the bartender asked, “What’ll it be, mister?”, would answer, “Just looking for a little information.”

Only, in this saloon, the real Gene Autry wasn’t looking for information. Tommy saw Gene, in modern-type clothes with a Western touch, sitting on a stool. A large drink perched half-finished in front of him. His eyes were bleary, and he was weaving unsteadily on the stool. “Aw, come on baby,” the real Gene said to a young woman sitting next to him. “Less go up t’ the room and get better acquainted. OK, hon? Aw, come on…”

“That’s enough!” barked the Gene that was with Tommy, as the boy stared, hardly believing his eyes. The tavern vanished on the instant, and everything spun crazily again.

When it stopped, they were in what was obviously a hospital ward. Tommy looked at the Gene who was with him. He had become more jowly, a few lines had appeared in his face, and his eyes looked bloodshot.

Tommy saw that the ward was in a children’s hospital. Many kids, some around his age, others younger or older, occupied beds on either side of a center aisle. But they were all sitting up, alert, smiling, watching as a man in a big white hat played a guitar and sang “Old Faithful” to them.

It was Gene, of course — Gene as he had been in those days. The Gene who was with Tommy said, “See that boy with the red hair? I’m right by his bed here. He was real sick, but he took a turn for the better right after my visit. Got over his illness. Grew up, married, raised a family.”

Tommy stirred, a little uneasy. “Gene, he — he looks a little familiar somehow. What’s his name?”

Autry smiled. “Tommy Chapman.”

Tommy jumped, startled, stared at the boy, then at the cowboy standing by him. “ME! But, that can’t be! I’m right here beside you! What — “

“Who were you named for, Tommy?” asked Gene, his blue eyes gazing into the boy’s.

Recognition suddenly leaped up on Tommy’s face. “Why, that’s — that’s my grandpa! I’ve never seen him before, except in family pictures! He died before I was born. I’ve gotta go talk to him!”

Gene quickly grabbed Tommy’s arm, gently but firmly.

“No, son, I can’t let you go over there. Believe me, it wouldn’t work.” Tommy struggled to break free and approach the other red-haired boy, but Gene wouldn’t yield. “Trust me. I know you’d like to talk to your grandpa, but how would you feel if you were 10 years old, lyin’ in a hospital bed, and a boy your own age ran up and told you he was your grandson?”

Tommy thought a moment, then laughed. “I’d probably freak out, bigtime,” he said.

Autry gently led Tommy away from the scene. “Come on, old pardner; we’ve got some more people to see,” he said. Tommy went — but he gazed back at his grandfather, who was watching and listening raptly as Gene Autry sang to him and the other kids.

The children’s hospital vanished. Suddenly the two were outside again on what looked like another movie set. There, arguing good naturedly with each other, Tommy recognized Smiley Burnette — paunchy, curly haired and clean-shaven; and Pat Buttram — paunchy, straight-haired and with scraggly whiskers — Gene’s two sidekicks, who never actually appeared in a movie together.

“Aw, what would they have needed you for when they had me — Mr. Total Talent?” said Smiley, pointing his finger at Pat. Buttram answered in his squeaky voice, “Now Smiley, you know they hired me because you run off from Gene and made movies with Roy Rogers and the Durango Kid. Besides, they saw I was so good they didn’t want you back anyway!”

“Yeah, sez you!” Smiley retorted. Then they noticed the three visitors.

“Well, hello, Gene,” Pat said. Smiley added, “I see you brought Tommy with you. Now Tommy, tell me, which of us was the better, funnier sidekick for Gene?”

The two men watched Tommy intently, their comic faces rapt with anticipation of his answer. Tommy stayed silent, not knowing what to say.

“Come on, boys, that’s not fair, to ask Tommy to make a judgment like that,” Gene said.

“Yeah — but I might ask him who was your prettiest leading lady!” said a throaty female voice from nearby. A lovely, shapely strawberry blonde woman was approaching, with her best smile beamed at the boy.

“Gail Davis!” Tommy exclaimed. “Why, you were the prettiest, Miss Davis!”

“Wise answer!” she said, laughing and giving him a one-armed hug as June Storey had. “This boy will go far — probably be a politician!”

Gail walked over to Gene and kissed him full on the lips. “How you doin’, hon?” she asked, as he gave a nervous glance toward Tommy, who stared, wide-eyed.

“Tommy,” said Gail, turning to look at him, “you picked a great guy to run with here, and that’s no lie. Gene Autry’s done a whole lot of things to help people in real life, not just in his movies.”

Autry motioned to Tommy. “We’ve gotta go again, son. Got more to show you.”

Frog, Pat and Gail all faded away as the two set off on Champ again at a gallop.

When the horse came to a halt again, they were on a city street somewhere. “Let’s get down,” Gene said. “I think somebody’s going to come along who’ll need to talk to me.”

The two stood, waiting, watching vehicles whiz past and pedestrians hurrying on their daily business. Before long, a middle-aged man approached — seedy looking, his shoes down at heel, his suit threadbare and shabby. The man needed a haircut, and his hat was old and stained.

“Hello, Bob!” called Gene to the man. “Why Gene — Gene Autry! I haven’t seen you for years — except on the silver screen, that is,” the man said, with a nervous laugh and a vigorous pumping of the cowboy’s hand.

Tommy thought, “He wants something from Gene; I can tell.”

The man attempted small talk for a couple of minutes, but he seemed to be trying too hard. Finally, sidling a little closer to Autry and lowering his voice, he said, “Say, Gene, I been kinda down on my luck for a long time now; can’t get a director’s job anymore — drinkin’, you know. Tryin’ to get back on my feet; wondered if you could spare me a little change, couple dollars or something …”

“Why, that’s the least I could do for one of my old directors, Bob,” Gene said genially. He reached into his left pocket, extracted two or three bills from a roll, slipped them into Bob’s hand. “Use it for things you NEED,” Autry said, staring hard into the other man’s eyes. “Know what I mean?”

“Yes, sir, Gene; I’m gonna get my life turned around, start paying my own way again,” Bob said, pumping his hand again. “Well, thanks, old buddy. You were always a pal. I’ll be seeing you!” Bob hurried off, the bills still clutched in his hand.

Gene watched him go, turned to gaze at Tommy. “He’ll be drunker than seven hundred dollars in about two hours,” the cowboy said sadly.

“Then why’d you give him the money, Gene?” asked the boy, mystified.

“Well, old Bob was good to me when I was getting started. Besides, he’s past saving. If I can make him feel good again for a few hours, then it’s a favor to an old friend, I reckon.”

Gene stood around, seemed to be watching for someone else. Soon another man dressed in cowboy clothes hove into view, walking briskly, head up, as if he were en route to an important appointment.

“Harvey, I haven’t seen you for years!” called Gene. Harvey looked at them, surprised, then hurried over to shake hands warmly with Gene. “You old son of a gun! You’ve done right well for yourself since I was your stunt man 20 years ago! You’re looking good,” he said.

“Well, we’re throwin’ a little ham in with the beans now,” Gene laughed. “How you doing?”

“Just fine!” Harvey said, a little too loudly. “Man, they keep me so busy with stunt work I don’t hardly have time to sleep! Yeah, life’s been pretty good to me.”

Tommy noticed Gene’s eyes flicking over Harvey, quickly and surreptitiously so as not to be obvious. Suddenly Autry looked up into the sky and said loudly, “Man, Harvey, what the heck kind of a plane is that up there?”

Harvey looked up, scanning the sky. Gene’s hand had been in his right-hand pocket. It snaked out quickly, slipped several bills into Harvey’s shirt pocket without his even noticing.

“Well, Gene, I sure don’t see any plane up there,” Harvey finally said. “I’ll be darned,” Autry answered. “Could have sworn I saw one. Maybe I better go to the eye doctor.”

Harvey laughed, said, “Well, gotta go, Gene. You take it easy, hear?” and hurried off.

Tommy looked at Gene curiously, puzzled by what he had just seen. “Gene, how come you slipped that money into his pocket, when he didn’t even ask you for any, and he said he was doing OK?”

Gene pushed the cowboy hat back on his head, regarded the boy for a minute. Then he said, “Well, for one thing I know Harvey too well to think he’d ever ask for help, even if he needed it bad. For another, he’s too old to still be getting stunt jobs. And third, ole’ Harvey was always real particular about his clothes. Well, I recognized that outfit he had on; he wore it one day when he was stunting in one of my movies, 20 years ago. He would have never done that if he was doing OK with money. He needed help, but he was too proud to ask for it. So I had to sneak it in while he wasn’t looking. I darn sure didn’t see any plane, either,” Gene said. He and Tommy both laughed then.

Tommy had been thinking about something. As they took off again aboard Champ, he looked around at Autry and asked, “Gene, aren’t you going to introduce me to your wife?”

Autry blushed a little, hesitated, then stammered, “W-why, sure, Tommy! We’ll head for my ranch house right now.”

Within seconds, they were standing in the living room of a large, gracious country home. There were western-themed pictures on the walls, throw rugs with Indian chiefs and prairie scenes on the polished hardwood floor, a large portrait of Gene and Champ above the ornate fireplace.

“Hello, Tommy! Gene said he was bringing you by,” said an attractive, kind-faced woman as she walked in from the kitchen. She took Tommy’s hand, saying, “I’m Ina Autry, Gene’s wife.”

“Gee! Hi, Mrs. Autry! I’ve heard your name from my dad, but I’d never seen a picture of you or anything,” Tommy answered. He decided on the spot that he liked Ina Autry a lot.

Minutes later, the three sat munching snacks Ina had brought from the kitchen. Tommy looked at her appraisingly, then asked, “How long you and Gene — I mean Mr. Autry — been married, Mrs. Autry?”

She laughed. “A long, long time.”

Gene leaned near his wife to take another couple of cookies from the plate on the table. As he did, she looked sharply at him, then said, “Tommy, will you excuse us for a minute? I need for Gene to help me with something in the kitchen.”

“Sure, Mrs. Autry,” the boy said. Gene arose with an uneasy look about him, following his wife out of the room. Tommy sat silently, nibbling at his cookies and listening intently. A minute or two passed. He could hear the Autrys talking in the kitchen, in voices lowered, seemingly to keep him from eavesdropping. But then Ina’s voice rise sharply. “Do you think I’m stupid? I can smell her perfume on you again!” “Honey, it was nothing. She was just talking to me and Tommy — ” “Sure,” she answered in sarcastic tones.

The boy heard a door close with a bang. Gene returned to the living room, looking crestfallen.

“Well, Tommy, Ina’s not feeling well. Come on, I want to show you something else — something good that people will remember me for, I hope.”

The two went outside, re-mounted Champ, with Tommy’s head now spinning with confusion. Had he picked the wrong hero? Was Gene Autry not such a great guy, after all?

They galloped through a mist that had suddenly descended. Then it cleared, revealing a large, white, California-Spanish building with a graceful belltower that looked like one on a Mexican mission. “What’s this, Gene?”

“This is the Autry Museum of Western Heritage,” Autry said, pride evident in his voice. “I built this so people could see what the history of the American West was really like — not just cowboy movies, but the real thing.”

They dismounted and walked through the front doors, which resembled the archway of an old-fashioned movie theater. Inside, Gene showed Tommy displays of Western art; of beautiful, intricately made antique firearms like those used in the days of old California; exhibits that highlighted the Native American lifestyle and art of the West; and of El Norte — the Spanish and Mexican North of Mexico.

There was also a section which featured pictures and information about the famous movie cowboys — including Gene; and where videos of Gene’s pictures could be purchased.

“Man! I’ve never seen anything like this, EVER before in my whole life!” cried Tommy, gazing about him after they had finished their short tour of the museum.

Gene smiled, put an affectionate arm around the boy’s shoulders.

“In future years, when I’m gone, I want people from all over the world who see this place to know the West was about a lot more than just a singing cowboy on a pretty horse,” Autry told Tommy.

As they returned to Champ waiting patiently outside, the Singing Cowboy added, “The real American West was all the things you’ve just seen, and a lot more, Tommy. But we’ll be adding new exhibits as time goes on.”

Time goes on. Tommy looked up at Gene as they stood beside Champion. The lines in the cowboy’s face were deeper now; his chin had doubled, and his neck looked scrawny, like a chicken’s — or an old man’s. Gene’s belly bulged over the ornate buckle on his cowboy belt, and his shoulders had a stoop that Tommy hadn’t noticed before.

“Gene, are you — uh, you look older. Are you OK?” Tommy said, real concern in his voice.

“Yes, Tommy, I’m alright,” came the reply — and the voice was pitched deeper, with a quaver it hadn ‘t had before. “Well, son, I AM older. It’s taken us longer than you might have thought to make this trip. You’re older, too, but you don’t realize it yet.”

“I am?” Tommy said, surprised.

“Come on, son,” Gene said, as he swung up onto Champ’s back — more slowly and awkwardly than he had before. He reached down, grabbed the boy under the arms and hoisted him up in front of him, panting audibly as he did so.

Champ trotted down the street, away from the museum. Suddenly Tommy realized that the horse wasn’t moving as easily as he had before, and he could see gray areas in Champ’s hair.

The familiar mist enveloped the three again, then cleared as Champ came to a halt.

Tommy looked around. They were somewhere on a gently sloping hillside, where cattle grazed peacefully in the near distance. Gene and Tommy could look down on a beautiful, blue river that wound around the landscape like the graceful curves of a snake. The boy could see a few small boats, moving slowly on the river, looking like the toys he used to play with in the bathtub.

Above and beyond the river were awesome, rounded mountains that resembled the domiciles of pagan gods. If Tommy had only been familiar with the Hudson River School of Art, he would have recognized a marked similarity.

“Let’s sit here in the shade and talk a while before we go on, Tommy,” said Gene, grunting as he climbed down. Tommy hopped off Champ and joined Gene sitting on the grass, looking around at the beautiful scene. “Gosh, I’ve never seen anything this gorgeous before,” the boy breathed.

“Got any questions for me, Tommy?” Gene asked. He had pulled a blade of grass and was sucking on it.

“Well — Gene, for one thing, how come all these people knew who I was? I’m just a little kid, and a lot of them lived years and years ago,” Tommy said.

“You see, Tommy, this was your tour — your adventure. It wouldn’t have been as much fun for you if nobody recognized you, would it?”

“No — I guess not. But there’s another thing, Gene. Why did you show me — well, you when you were drunk, and when you were going into the hotel room with that lady, and Gail Davis kissing you like grownups kiss when they’re — well …”

“Because, Tommy, I wanted you to see the real Gene Autry — the bad things as well as the good. You see, little pardner, you’ve made me your idol. That’s pretty flattering to anybody. But even good guys sometimes do bad things. Nobody’s perfect. Even singing cowboys sometimes misbehave — just like 10-year-old kids do. It’s not that any of us want to be bad, or do things we know aren’t right. But we’re human — and humans make mistakes. You see what I mean?”

Tommy nodded. He WAS beginning to see.

“But the good things you did — making people believe in doing right, singing for them, visiting sick kids, helping out old friends when they needed it, opening the museum — those kind of outweigh the not-so-good things. Is that it, Gene?”

Autry smiled. “Yes, Tommy, that’s the way I hope it is. You’re a pretty smart young man — I thought you’d understand what it was all about.”

Tommy sighed, looked around at the landscape, then gazed at Gene again. “I can’t wait to tell my friends about all this. Wow! What a story!”

Autry smiled, shook his head. “You can tell them, Tommy, but they won’t believe you. They’ll claim you made it up because you’re a big Gene Autry fan. Or they’ll say you must have dreamed all of it.”

Dream. The word ignited just a tiny spark of disappointment in Tommy’s mind.

“Gene! Was this all — was it just a dream? Am I just dreaming, right now?” he asked anxiously.

“Tommy, we’ll talk about all that at our next stop, when we — ” Suddenly Autry stopped in mid-sentence, looked up just over Tommy’s head. With a surprised expression, Gene said, “What? Well, not yet, though. I’ve got more things to show and tell Tommy! No! Not yet!”

Tommy looked quickly over his shoulder. He saw no one — nothing but the blue, cloudless, afternoon sky.

Gene seemed to be listening to some voice, inaudible to Tommy’s ears. Finally the old cowboy sighed. “Well, then I guess that’s it,” he said, rising slowly to his feet. Tommy looked up at Autry, dumbfounded — and found that he had suddenly become a very, very old man, quaking unsteadily on his feet. “Tommy,” he said in a quavering, geezer’s voice, “Champ and I have got to go.”

Tommy jumped up, filled with foreboding. “OK, Gene — where we going now?”

The old cowboy’s face was wreathed in sadness. “Sorry, little pard, but you can’t go with us this time. Just close your eyes and count to 10, and you’ll be back in your bedroom. I don’t like leaving you like this, but … you see, Tommy, sometimes things in this life don’t go like you plan.”

“Gene! No! Don’t go! Don’t leave me here!” cried Tommy, suddenly feeling like a very small, soon-to-be-abandoned child, alone in the wilderness.

“I’ve got to go, Tommy! I can’t stay any longer! But listen — I’ll be in touch with you again. That’s a promise. Bye, Tommy!” Champ reared — but seemed to have trouble doing it — and aging horse and rider galloped off, toward the afternoon sun, becoming smaller, smaller — Tommy couldn’t tell whether they were finally too far away for him to see, or if they had just disappeared.

The boy was frantic now. He ran up and down the hillside, screaming, “Gene! Mommy! Daddy! Help me! Don’t leave me here!”

Suddenly he felt a strong wind blowing into his face. It blew harder, stronger — finally it swept him off his feet, and backward — backward — and then scenes started to reverse past him on either side, like a videotape being rewound. He saw the museum, the Autry home, Bob and Harvey, Smiley, Pat and Gail, all the scenes he and Gene had visited, going by in reverse, with their voices going backwards, assaulting his ears like some weird, snarky foreign language.

Then — Plunk! He landed flat on his butt on the floor of his bedroom.

Dazed, confused, and very, very sleepy, Tommy staggered up from the floor, crawled into his bed, pulled the covers over him, and fell fast asleep.

Hours later, Tommy began coming back to consciousness. Someone was shaking him insistently.

“Tommy? Tommy! Wake up, son.” It was his dad. Tommy stirred, opened his eyes, looked into those of his father.

Art was somber; shaken; like a man who was going to have to make a painful announcement.

“Tommy,” said Art, his sad eyes gazing into those of his son. “Tommy, they just said on the TV news that — that Mr. Gene Autry died yesterday.”

Disbelief dawned in the boy’s eyes. “No — he can’t be — I just –” … Suddenly Tommy’s shoulders began to shake with sobs. He turned over, buried his face in his pillow, cried unashamedly. “Oh, Gene, you were the best! The absolute best! You can’t be dead — you just can’t be!”

Art stood with his hand on his son’s shoulder for a minute, but feeling that a good cry undisturbed might be the best medicine, he said, “I’ll be right in the other room if you need anything, son.”

Tommy wept until he was finally cried out. He sat up in bed then — thinking of what he remembered of the previous night, of whether it was a magical journey, or just a dream — and of what Gene Autry had said: “I’ll be in touch with you again.”

Finally the boy showered, started to put on his cowboy outfit as usual — then pulled some regular clothes from the drawer instead. He wasn’t sure why — it just seemed like the thing to do.

Sad-faced but composed, Tommy came downstairs, walked through the kitchen. “Honey, I’m sure sorry about Gene Autry,” said Molly. “I’ve got your breakfast ready.”

“Thanks Mom, but I’m not hungry. I’m gonna go out and curry Little Champ — and tell him about Gene,” said Tommy. As he continued on out the back door. his mother looked him over. “My goodness — I don’t remember him being that tall yesterday,” she thought. “Time for bigger clothes again.”

Tommy approached his pony’s stall. Little Champ looked at him with his head up and eyes bright, as if to say, “See what I’ve got?”

The boy glanced, and stopped, stunned.

Little Champ was wearing a bridle — a brand-new bridle. It had the twin six-shooters with pearl handles permitted only for Gene Autry’s horse.

There was a note attached to the bridle. Tommy looked at it and read,

“Hi, little pardner. Told you I’d get in touch again. Champ has given his express permission for your pony to wear this replica of Champ’s one-of-a-kind double pistol bridle. May he wear it many years in good health; and may you grow up to remember that none of us are perfect, but to be a worthy cowboy your good deeds must weigh a lot heavier in the balance than your bad ones.”

Tommy’s legs gave way, and he sat straight down on the garage floor with a bump. Little Champ looked sidewise and down at him. Then he went, “Wheehuhuhuhuh!” In spite of his shock, Tommy giggled. “That sounded like a horse laugh to me,” he said.

He looked up at the pony, finally said, “Well, aren’t you gonna help me up? No? Didn’t think so.”

Tommy got to his feet, examined the new bridle. It was real, all right. What other unbelievable things would this night and day bring? he wondered.

He took the curry comb, began using it on Little Champ. As he stroked the sorrel’s back, he said to the pony, “Old boy, I just wish you could talk!”

Tommy went back up to the house in a little while; he decided not to say anything to his parents about the bridle, since he couldn’t explain it anyway. Besides, he didn’t want to find out something that would spoil the wonderful buzz the events of the last few hours had given him.

As he passed the phone in the hall, it rang. Tommy knew who would be there before he picked it up.

“Hi, Conchita.”

“Tommy! You guessed it was me!”

“Yeah — just a feeling I had, with what happened yesterday and all. I guess you’ve heard about Gene?”

“Yes.” He could detect little half-suppressed sobs as she talked, so he knew she had been crying, too.

“Conchita — wanna come over? I’ve got something to show you.”

“Yes, I do. But first, Tommy, I’ve got to tell you about the most wonderful thing that happened to me last night! I was sitting on my bed, wishing I could see Gene Autry just once, like he was when he made the movies …”

The same fantasy — or dream — or magical happening. Tommy listened, letting Conchita tell it all, because he knew it was important to her. There were a few minor differences, maybe because she was a girl and he a boy; but basically they had trod the same path.

When she was finally finished, Tommy said, “Conchita, you’re not gonna believe this …”

Later that day, Conchita’s grandmother drove her over to the Chapman farm. The two children were soon out at the garage, occupied with the pony.

Molly happened to look out the window and saw Tommy and Conchita riding double on Little Champ. She sat in front and he behind. His arms were around her waist, he whispered into her ear, and she was giggling.

Molly looked the pony over, then realized that something appeared different.

“Art, where did you find that new bridle for Little Champ? The one with the two guns on it?”

“What?” said her husband in surprise. He walked to the window, peered out. “Well, I’ll be damned. Tommy said he couldn’t have a bridle like that because Gene Autry’s horse was the only one allowed to wear one, so I didn’t think anything more about it. It’s damn sure on the pony now! Are you sure you didn’t get him that bridle?”

“Me?!” his wife asked. “I didn’t even know about any special bridle or anything like that. I sure hope he didn’t swipe that from somewhere.”

“I doubt that,” Art said. “Maybe it’s better we just don’t worry about it.” He thought for a minute, then mused, “You know, honey, I read somewhere once that magic is when something can’t be explained by any natural means. Huh?”

“Oh, that’s nonsense!” Molly declared. Then she pondered, and added, with less conviction, “Isn’t it?”

The two children rode Little Champ around behind the garage, and Tommy said, “Conchita, let’s stop and get down for a minute. We need to talk.”

They dismounted and sat facing in the grass.

“Whatever it was that you and I went through last night, nobody will believe us if we tell them,” Tommy said. He gazed into Conchita’s eyes, and she gazed right back. “Yeah, I guess you’re right. But I’d sure like to tell Grandma!”

“I’d like to tell my folks, too, Conchita, but they’d just say I dreamed it, the same thing your grandma would say. Maybe it WAS a dream; but maybe it wasn’t. Gosh, it seemed so real, like I was right there! Was yours the same way?”

“Yeah, it sure was,” Conchita said, her eyes growing dreamy. “I could feel things, smell things; not just hear and see them. I could even smell Gene’s cologne!” She giggled, a little embarrassed.

“Yeah; like Mrs. Autry could smell Gail Davis’s perfume,” Tommy added. They both laughed at that.

So they decided that the events of the previous night would remain theirs alone; no one else would ever find out. They sealed the pact with a warm hug, and a kiss.

When Conchita arrived home at suppertime, and went into her bedroom, she found a surprise: On her bed was a flat package of some sort.

She picked it up and looked at it. One end of the package was open. Inside, there was a disc that looked vaguely like a large CD — but old. Very old. She slid her hand inside the package, pulled the disc out — and a note fell onto her bed.

“Hi, sweetheart. Many years ago, I hid the master disc for a Mexican song I’d recorded because it was too beautiful for just everyone to listen to. I wanted to save it for someone really special. You are that person, Conchita. Hope you and your grandmother Esmerelda enjoy listening to ‘Noches Eternas.’ You’re the first ones to hear it in over 65 years.”

Conchita’s eyes popped. She read the note again. When the full import of it struck her, she screamed long and loud, almost dropping the fragile record — onto the hardwood floor! She caught it just in time, hugged it to her chest, and ran from the room yelling, “Grandma! Grandma! We’ve got ‘Noches Eternas!’ Ge — er, somebody left the master disc on my bed!”

She found Esmerelda doing the laundry, showed her the disc. The old lady looked thunderstruck. ” ‘Noches Eternas’?” she said, her voice quavering with emotion. “Are you certain that’s what it said? And, you mean someone was in the house?”

“Yes, Grandma; here’s the note right here,” said Conchita, holding it out to her. “But, no, I didn’t see anyone; nobody at all.”

The old lady examined the note, nodded her head slowly as she read the message.

Luckily there was an old 1950s-era record player high up on a shelf in the closet. It would play the disc.

Soon, they both sat listening to a very young Gene Autry, singing a mesmerizing Mexican “ranchera” in excellent Spanish in his high baritone, his vibrato a beautiful trill. Conchita sat hunched over with her face toward the record player, her eyes wide; her grandmother rocked slowly in her chair, humming the classic Mexican tune gently, a few tears coursing lazily down her wrinkled cheeks.

The song ended, all too soon. Esmerelda continued rocking, sighed softly with contentment. Conchita hopped up, took the old photo of Gene Autry from the vanity and held it reverently, studying the young singing cowboy.

“Wow! Gene Autry sure was good lookin’ in those days,” she said. “Bet he had a lot of girlfriends!”

Esmerelda stopped rocking abruptly. As Conchita stared, the old lady’s face seemed to transform from elderly duena back to that of the young senorita she had been many years before. Her eyes sparkled and her cheeks glowed for a few seconds as she stared off into space, seeing things visible only to her.

Then she slowly began rocking again as her face returned to old age. And she said softly, “I know of at least one he had!”

2 comments for “Tommy and Conchita’s magical journey”