It must be the time for old, classic silent movies. “The Artist” and “Hugo” won a bushel of Oscars between them at the Academy Awards; and after many years of waiting and wanting, I finally got to view Buster Keaton’s “The General.”

It must be the time for old, classic silent movies. “The Artist” and “Hugo” won a bushel of Oscars between them at the Academy Awards; and after many years of waiting and wanting, I finally got to view Buster Keaton’s “The General.”

If you’re, say, under 50, you’re probably saying, “Whose what?”

Pull up a chair, youngster, and let me tell you about “The Great Stone Face,” which was Keaton’s nickname when he was quite possibly the greatest American movie comedian of the silent era. Oh, sure, Charlie Chaplin got all the glory, but many film historians believe that, for sheer inventiveness, talent, and energy, Keaton was the tops.

Joseph Frank Keaton Jr. was born in 1895 in Kansas, to a vaudeville acting couple, Joe and Myra Edith Cutler Keaton. For those of you reading this who are fellow Hoosiers of mine, Joe Keaton Sr. had Indiana roots; he was originally from Vigo County; that’s Terre Haute.

When young Joe was just a toddler, he took a header down a flight of stairs while a good friend of his dad’s named Harry Houdini (yes, THAT Houdini) was visiting his parents. Apparently neither adult Keaton, nor Houdini, was close enough to catch little Joe, who landed at the bottom of the stairs, got up immediately, and went on about his business. “Man, what a buster that was!” said Houdini, using the vaudeville term for a spectacular fall that could have resulted in serious injuries. But little Joe shrugged it off as if nothing had happened. Somehow, the nickname “Buster” had found a home, and young Keaton who would appear in scores of comedy movies, never would be known as anything else, except among family and close friends.

Joe and Myra Keaton’s vaudeville comedy act was very physical; a lot of it consisted of Joe throwing little Buster around like he was a sack of flour. Buster had been born with a talent for “taking” a fall without hurting himself, and would often grin or laugh when he was thrown across the stage. But when Joe and Myra realized that the act got more laughs when Buster kept a “poker face” during his flights through the air, they impressed upon little Buster that he must keep a straight face while flying through the air and landing. Hence, keeping a solemn, expressionless puss became second nature to the young entertainer.

As a young adult, Buster Keaton left vaudeville and traveled to Hollywood to try to make his fortune. Becoming a protege of the famous, portly comedian Fatty Arbuckle, he got his start in Arbuckle’s 1917 feature, “The Butcher Boy,” in which he got hit in the face with a sizeable sack of flour thrown by Arbuckle. When they were filming, Keaton asked Arbuckle, “How will I know how to time that when you throw the sack?” Arbuckle said, “When I say your name” (the films were still silent, don’t forget) “just look up, and it’ll be there.”

He did. It was.

Keaton continued making films up into the 1920s, using his extreme dexterity and ability to do all his own stunts (he was part acrobat, part mountain goat) to trademark his own unique style of very physical comedy as a plucky young man who never smiled, but often “got the girl” (women found the young Keaton’s frozen features quite handsome), and who was unendingly resourceful in extracting himself from many a perilous and dangerous situation.

Starting in about 1920, Keaton began directing his own features. Several of them in the next several years are considered among the best comedies ever filmed, among them “Sherlock Jr.,” “Our Hospitality,” and “The Navigator.”

Finally, in 1926 (or 1927; records differ on the release year), came his masterpiece.

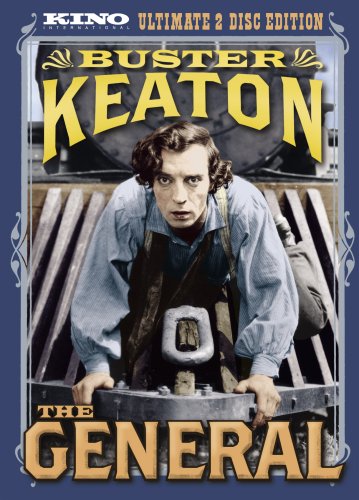

“The General”

Johnny Gray is a railroad engineer in Marietta, Ga., during the Civil War. When the call comes for enlistments into the Confederate Army upon the firing on Fort Sumter, he is first in line at the enlistment office, taking short cuts to get there ahead of everyone else. But due to his occupation, the enlistment officer won’t take him, as he’s considered “more valuable” to the Confederacy running troop trains. But the reason for his rejection is not told to him, and later his girlfriend, Annabelle Lee (played by Marion Mack), her father and brother all turn their backs on him as being a “draft dodger.” Annabelle Lee says she will never marry him until he wears the Confederate uniform.

Some time later, in 1862, Union Army spies steal Johnny’s engine, The General, and its attached train from the station during a lunch break. They intend to link up with an approaching Union force and cut the telegraph and railroad lines relied upon by the Confederates.

Johnny rallies other Southerners and seizes another train to pursue the Yankees. The others, unable to get on the speeding train, give up the chase, and Johnny is left, unaware of their absence, to pursue alone. The chase goes on for almost the entire rest of the movie, with Johnny eventually rescuing Annabelle Lee from the boxcar on the fleeing train, after which she joins him in the attempt to get The General back and foil the Federals’ plans.

After some harrowing twists and turns, the other engine, now occupied by some of the Yankees, starts across a bridge leading to the camp of the Confederate force — but Johnny has gotten there first, and set the bridge on fire. It collapses beneath the weight of the engine, and train and Yankees all plunge into the river below. The bulk of the Union force then attacks across the river, but the Confederates drive them back and force a retreat. And Johnny gets back his beloved General.

The final scenes of the movie show Johnny Gray being enlisted into the Confederate Army — as a lieutenant — as a reward for his courageous actions in saving The General and helping to foil the Yankee plot. As he and Annabelle Lee sit on the drive shaft of the General, wishing some privacy because now they are going to marry, a stream of Confederate soldiers marches past, each saluting Johnny smartly. He finally moves around so that his right arm is on the outside, then proceeds to return the salutes repeatedly, while kissing his beloved Annabelle Lee.

The film might sound like just another chase movie in the telling — but if you get to see it, you’ll understand why it was Keaton’s masterpiece. His physical dexterity is simply amazing, as he at one point rides the cowcatcher of the other engine in order to kick loose railroad ties out of the way which might cause a train wreck; as he runs nimbly along the top of railroad cars back to the engine while it is in full flight; and as he uses an axe to knock the rear end out of the last boxcar so that he can throw railroad ties from it at the now-pursuing Union troops.

The crash of the other locomotive into the river is one of the classic moments of silent film. No trick photography or miniatures were used — the locomotive actually fell with a collapsing bridge, into a river in the state of Washington, the site of the filming. The engine stayed there, a local landmark, until it was scrapped out for needed war material during World War II.

Marion Mack appears to have done most of her own stunts in the movie, too, and that involved some serious agility and willingness to look decidedly un-pretty and un-feminine.

Three Union generals — unnamed — are shown in the film, discussing how to take advantage of the raiders’ theft of The General. One of them is Joe Keaton, Buster’s dad.

“The General” did not do well at the box office upon release, and its poor showing caused Keaton to lose a lot of control over his own features from that point on. By the 1930s he was starring in comedies directed by other people, having to do what they wanted, instead of what his directorial and comic instincts told him was right.

He developed a drinking problem. He continued to appear in movies, nevertheless, on through the 1940s and into the ’50s. Keaton appeared on numerous TV shows, and his career culminated with his portrayal of an ancient Roman who spends most of the movie running around the perimeters of the city, in “A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum,” released in 1966.

Buster Keaton died that same year, of lung cancer, at age 70.

In 1958, a movie of his life, “The Buster Keaton Story,” was filmed, starring Donald O’Connor. The script called for re-creations of a number of scenes from Keaton’s comedies. O’Connor, a young man then and a very talented dancer, was expected to have no problem doing the stunts.

But here’s irony for you: Some of the stunts had to be scrapped, because O’Connor, young and athletic as he was, simply could not do them convincingly. When the filmmakers consulted with Keaton about the stunts, he said, “I could still do them for you if you want me to. But I can’t look 30 years old any more!”

Among best 20th Century films

Opinions of “The General” changed drastically over the years. In a 2000 poll, it was chosen as the 18th best movie of the 20th Century on the American Film Institute’s list of 100 Greatest American Movies. In a “Sight and Sound” poll of 2002, “The General” was named as 15th best; in another poll, the seventh best.

The greatest tribute came in yet another poll, on silent movies. “The General” was chosen as No. 1 — the top silent film ever made. “Sherlock Jr.” came in at No. 13.

Perhaps the most significant individual comment about “The General” came from a filmmaker who knew a few things about great movies himself. Orson Welles once said, ” ‘The General’ was the greatest comedy ever made, the greatest Civil War film ever made, and perhaps the greatest FILM ever made!”

Coming from the director and star of “Citizen Kane,” that was high praise, indeed.

I think we can assume that somewhere, Buster Keaton is finally smiling.

4 comments for ““The General” ranks high among all movies”